Guard housing levy cash for intended aim

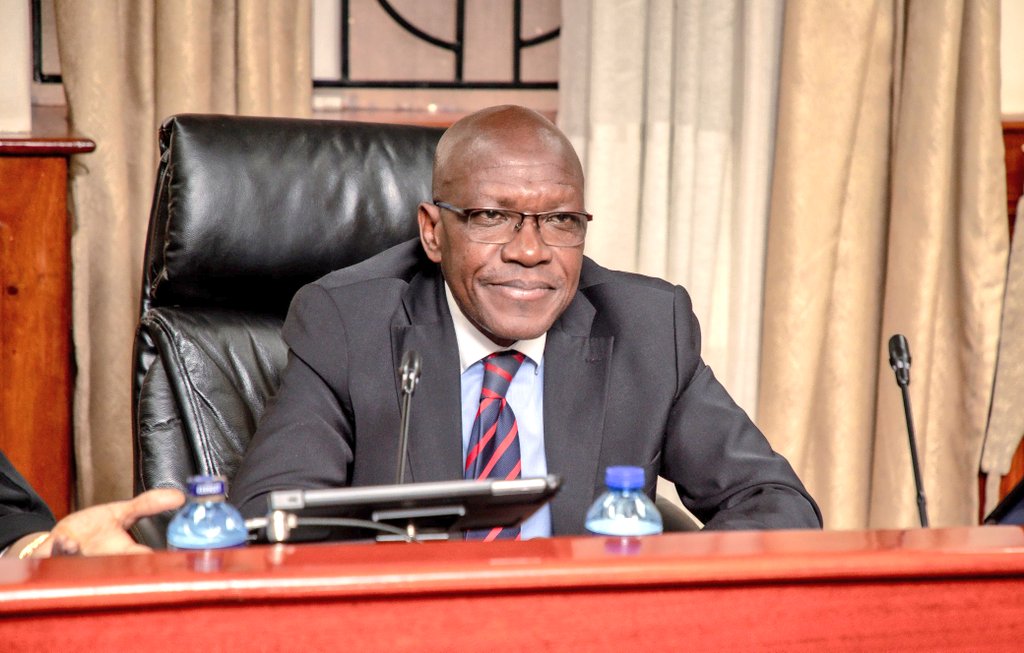

COTU Secretary General Francis Atwoli is embroiled in a very unseemly spat with Housing Principal Secretary Charles Hinga over the government’s supposed intention to expand the use of the housing levy beyond affordable housing.

The first thing that one wonders is why such high-profile figures, who hold a lot of public influence, cannot spare the public all these emotional outbursts and reach out to each other to resolve the problem.

Atwoli and Hinga are definitely on speed dial, probably even on first-name terms.

And if they cannot resolve the issue themselves, there are layers upon layers of official and private channels they can use to come together and find a solution.

But no, they have to have the ego-fuelled spats in public.

The controversy should instead be a vehicle to bring all stakeholders on board to affirm why the government has been deducting the housing levy from employees, and embed in law the objectives to ensure there is no siphoning off to other government activities.

The housing levy was introduced to finance affordable housing throughout the country.

The huge need for housing in Kenya has been frustrated for a long time by expensive credit for mortgages, very expensive houses put up by private developers, and the high cost of plots, especially in urban areas.

The programme took off in earnest, and there are projects across all 47 counties, with 140,000 houses currently under construction.

Indeed, the first set of tenants has started moving into houses recently completed.

The interesting thing is that both combatants have a point.

Atwoli says the government should not utilise the housing levy for its other infrastructure projects, which have been taken care of in other budget vote lines anyway.

This is a valid point, as the government’s tough financial position may easily sway it to dip its fingers into this huge cache of money it sees as ‘idle’.

Hinga says that amenities like markets that are being built alongside the projects are meant to serve the communities that will be living there.

This makes a lot of sense.

A community of 15,000 families in a project will require a commercial shopping centre to serve it alongside schools, maybe even a police station. The affordable housing projects are creating entirely new communities from scratch.

If these two men and the other stakeholders were really interested in resolving this, a solution could easily be found.

The bottom line is that the affordable housing programme has started benefiting those for whom it was meant.

Indeed, the Social Housing Fund, which is intended to eliminate slums by offering slum dwellers mortgages for modern houses at rates equivalent to the meagre house rents they have been paying, is really a revolutionary development initiative.

The government is salivating at the huge amounts of housing levy funds that are “lying idle” due to capacity constraints.

Housing projects take years to put up. However, it should be seen as a long-term initiative that will even transcend governments, and be utilised well into the future until all slums are gone, and there is enough stock of housing to satisfy the huge deficit in the low-income and lower-middle-income markets that are completely ignored by commercial developers.