Death of Kasipul MP paint chilling image

Kenya’s political history is marred by unresolved episodes of violence—from high-profile assassinations to everyday tragedies—that have slowly eroded public trust in the State’s ability to deliver justice.

The recent assassination of Kasipul Member of Parliament (MP) add to a long list of political figures that have gone down. History rightly records that the assassination of Pio Gama Pinto in 1965 was not just the silencing of a freedom fighter—it marked the beginning of a disturbing pattern.

The killings of Tom Mboya in 1969, J.M. Kariuki in 1975, and Robert Ouko in 1990 followed, each deepening the national wound and highlighting the fragility of justice in post-independence Kenya. These high-profile assassinations were seldom followed by credible investigations, leaving a trail of unanswered questions and feeding a culture of silence and impunity.

Beyond politicians, the cycle of insecurity has touched other pillars of society. In 2021, Agnes Tirop—an Olympian and rising national star—was murdered, drawing attention to broader vulnerabilities in society. Her killing, while categorized as domestic, raised questions about institutional inaction and the societal systems that often fail to protect even the most visible citizens.

Human rights defenders have also faced life-threatening risks. The abduction and killing of lawyer Willie Kimani, his client Josephat Mwenda, and their driver Joseph Muiruri in 2016 in a well-orchestrated plan exposed gaps in oversight and accountability within law enforcement circles. Their deaths were not isolated acts of violence; they represented a breakdown in the protection of fundamental rights.

Similarly, countless ordinary citizens in marginalised regions have borne the brunt of insecurity. In the North Rift and parts of northern Kenya, recurrent bandit attacks have claimed numerous lives—schoolchildren, elders, and pastoralists among them. These tragedies often go underreported and under-addressed, reflecting a gap between policy declarations and action.

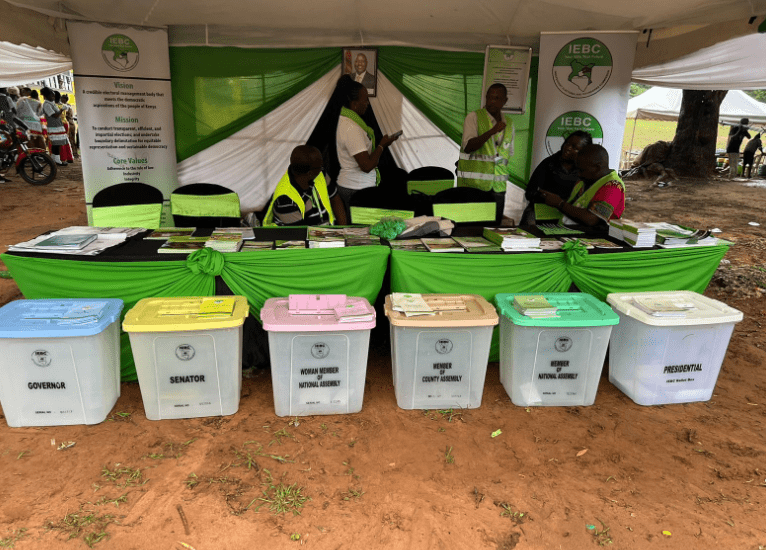

Protest-related violence is another area of concern. During the June 2024 protests against the Finance Bill, several young people—including Rex Kanyike in Nairobi—lost their lives. These incidents, though brief fixtures in national headlines, point to systemic issues in how dissent is managed. From the post-election violence of 2007–2008 to the 2017 anti-IEBC demonstrations, lives have been lost in the exercise of democratic rights but little has been made to address the cases of loss of live safe for the political pronouncement which is followed with little action.

A dangerous normalcy

When MP Charles Ong’ondo Were was gunned down by a gunman on a motorbike, there was no national gasp. Instead, there was a pause, then a sigh, then the script: mourning, condemnation, a promise to investigate, and predictably, silence will follow judging by the previous similar incidents. In that silence lives a dangerous normalcy—the quiet admission that violence has become part of our national fabric.

Kenya’s collective response to such tragedies often reveals a societal pattern: “we move on”. In the wake of these events, social media briefly fills with hashtags, condolences, and outrage—only to return to routine.

As Bashir Abdullahi, MP for Mandera North, while contributing in Parliament concerning the BBC documentary “Bloody Parliament”, bluntly remarked, “People were killed, but we sympathised and moved on.”

The phrase has become a common refrain—a symbol of national coping, but also of detachment.

This desensitisation extends beyond the political elite. When MP Beatrice Elachi lost her son under tragic circumstances, the public reaction was not unified mourning but a flurry of insensitive commentary online. These responses point to a troubling erosion of shared empathy and a growing inclination to consume grief as spectacle.

When President Ruto made a tour of the city, thugs descended on motorists and people going about their business just within a few kilometers from where the President was addressing attendees of his rallies. What is disturbing is—if thugs can’t even fear the most protected in the land, then there is something amiss.

What processes are set in motion after such losses? Investigations are promised, but few yield convictions. Commissions are formed, but their findings often gather dust. Families mourn privately, and public memory fades. This cycle raises pressing questions about institutional will and public accountability.

Crisis of confidence

Members of Parliament, too, have contributed to this crisis of confidence. Some have been so reckless in their pronouncements that they invite public scorn. The now-infamous “move on” remarks, though seemingly casual, compel us to reflect on the deeper culture we have become accustomed to—a culture where impunity and resignation coexist.

These challenges demand a reconsideration of State responsibility. Institutions must not only respond to violence but anticipate and prevent it. The security of all citizens—regardless of social status—must be guaranteed without delay or discrimination.

When threats against public figures are made, they should trigger immediate, verifiable responses from law enforcement. When activists or whistleblowers report danger, their protection should not depend on public protest. And when ordinary citizens perish in violent circumstances—whether in remote villages or city streets—justice must not be an afterthought.

This is not a call for alarm, but for institutional introspection. Kenya has the legal architecture to address these concerns. What remains is the need to strengthen the implementation of existing laws and improve oversight structures. Independent investigative bodies, better protected whistleblower mechanisms, and a depoliticised police service are all necessary reforms.

Moreover, national memory must be preserved. A democratic society should not forget its history of violence or treat it as episodic. Each name—whether of a politician, a protester, or an unknown villager—deserves a place in the collective narrative. Their stories should inform future policies, not be lost in past silences. Ultimately, the question is not only about security but also about legitimacy. A State that protects its people earns their trust. A government that values life—regardless of geography or status—secures its future.

Kenya stands at a intersection. If the culture of silence and impunity persists, it risks alienating its own citizens from the institutions meant to serve them. But if this moment inspires reform—quiet, steady, and deliberate—then the path to national cohesion and justice remains open.

This future depends not on grand pronouncements but on consistent, measured actions rooted in principle. Because the opposite of fear is not just courage—it is justice. And justice, in the end, is what binds nations together. Only through justice can we undo the quiet crisis that has settled over Kenya—a crisis not of headlines, but of trust lost, voices silenced, and wounds left open.

The writer is a History Lecturer & UASU Chapter Trustee, Alupe University-Kenya