UhuRuto fallout, Handshake to shape presidential contest

The August 9 presidential vote is mostly a two-way battle between Deputy President William Ruto and Azimio- One Kenya candidate Raila Odinga.

Odinga is a veteran politician who served a long spell in detention in the 1980s for his agitation for multi-party democracy at a time when Kenya was still under strongman rule. He hopes to finally clinch the presidency after several unsuccessful bids. The 77-year-old commands name recognition throughout much of Kenya and has a loyal support base, particularly in cities, the west, parts of the east and the Coast. He hopes that President Uhuru Kenyatta’s backing will help him draw support from the Kenyatta-Ruto Jubilee party base, which propelled the incumbent to victory in the previous two elections.

Ruto, 55, has been deputy president since 2013. Over the past four years, the energetic campaigner has rallied significant sections of the Kenyan electorate to his side, casting himself as a self-made everyman who understands the grievances of the poor. Though one of Kenya’s wealthiest politicians, he draws a contrast between his humble background and the privileged upbringings of Odinga and Kenyatta, both of whom come from political dynasties and have throughout their careers benefited from considerable family fortunes.

ICC cases

He positions himself as a “hustler” in tune with Kenyans struggling to earn a living, unlike his opponents whom he casts as out-oftouch scions of Kenyan aristocracy. Ruto has confounded many pundits by establishing a firm foothold in Kenyatta’s Mount Kenya home region. Many important political figures from this area back his campaign.

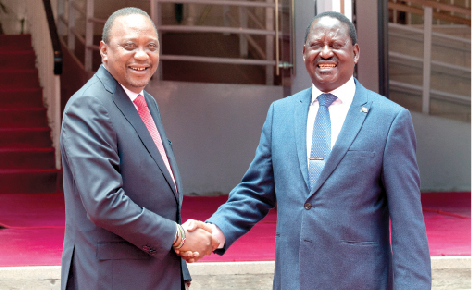

Despite his efforts to distance himself from Kenyatta and Odinga, however, Ruto is himself part of Kenya’s rent-seeking elites. Kenyatta and Ruto formed a formidable alliance in 2012, appearing to be such close friends that the public dubbed the inseparable duo “UhuRuto”. That union brought together their populous voter bases, the Kikuyu and Kalenjin ethnic groups, respectively, allowing them to navigate their way to victory in March 2013 elections.

At the time, the International Criminal Court had indicted the two for allegedly whipping up ethnic violence in 2007-2008. Prosecutors later dropped the cases. The precise source of the rift between Kenyatta and Ruto is difficult to pin down. In early 2018, only a few months after Kenyatta and Ruto bested Odinga to win a second term in the contentious 2017 election – which wound up in front of the courts – relations between the President and his deputy rapidly deteriorated. It was then that Kenyatta forged a sudden alliance with his erstwhile opponent Odinga, ostensibly to calm tensions in the country, but also sending a clear signal that he would not back Ruto as his successor.

Personal fortunes

Since then, the two have repeatedly accused each other of betrayal, but neither has offered a satisfactory explanation for their falling-out. An insider from Kenyatta’s camp said the president was concerned that a Ruto presidency would “spell disaster for Kenya”, citing past corruption allegations that have dogged Ruto’s career. Kenyatta himself has offered a variety of reasons, including that he was miffed that Ruto resisted his alliance with Odinga and began campaigning for the presidency early on.

Ruto camp insiders claim that Kenyatta sidelined his deputy because he wants to protect his family’s extensive business interests, some of which are intertwined with the state, from an unpredictable Ruto presidency.

In this telling, the Kenyattas feel they will be safer under an Odinga presidency than one led by the younger and more ambitious Ruto. Although often unspoken, protecting the personal fortunes of politicians and their families is a key concern in Kenya’s succession politics; virtually all major politicians, including Kenyatta, Ruto and Odinga, own large plots of land and a range of lucrative companies. This issue is the one that raises the stakes in Kenyan elections and the reason why political figures tend to view electoral contests as existential.

Ruto coyly referred to it in March, when he suggested he would protect Kenyatta’s legacy if he becomes president.

Ruto and his circle also accuse Kenyatta of duplicity and betrayal. Ruto cites his many years of support for Kenyatta, notably in the 2002, 2013 and 2017 election seasons. His supporters often replay Kenyatta’s public assurances on the campaign trail that he would back Ruto’s candidacy in presidential elections later on. For instance, during his first term, Kenyatta famously declared in Kiswahili that he would support Ruto after two terms in office, saying: “Yangu kumi, ya Ruto kumi” (“Ten years for me and ten for Ruto”).

The Kenyatta-Ruto schism has dominated the Jubilee administration’s second term, with implications for a key goal of the Kenyatta-Odinga alliance that emerged in 2018 – enactment of the Building Bridges Initiative (BBI). BBI was a proposal to introduce constitutional changes through a referendum in order to expand the Kenyan executive and, the proponents claimed, to step away from Kenya’s winner-takeall politics by creating more seats at the table.

Limited tensions

The falling-out between Kenyatta and Ruto has played out prominently in the Mount Kenya region, the country’s most populous electoral constituency and Kenyatta’s political base. The region is populated primarily by the Kikuyu, Kenya’s largest ethnic group. In one of the more confounding features of the 2022 electoral cycle, Ruto, a Kalenjin, has brought many of Kenyatta’s traditional Kikuyu supporters onto his side through his spirited campaign. In 2021, his UDA party won several parliamentary and ward by-elections in the region against Kenyatta-backed candidates. Many in the region cite the need to repay Ruto’s earlier loyalty to Kenyatta to explain their decision to stick with Ruto.

There is a benefit to this dynamic: while acrimony between national politicians has in the past stoked inter-ethnic tensions and election-related violence, the Kikuyu’s surprising embrace of Ruto in both Mount Kenya and the Rift Valley means tensions between the Kikuyu and Kalenjin have thus far been limited.

Whether the calm endures in the immediate aftermath of the election will depend to a large extent on politicians’ behaviour, however. Although the falling-out between Kenyatta and Ruto follows a well-worn pattern of shifting alliances among Kenyan elites, there is widespread (and reasonable) concern about the extent to which one candidate or the other might try to game the system given the perceived sky-high stakes of the vote for both. For Kenyatta, that could mean using state power to influence the election, while for Ruto’s camp, it could mean mobilising street protests to reject an unfavourable outcome.

In some respects, the enmity between Kenyatta and Ruto has left Odinga in an awkward position, but he is working assiduously to parlay it to his advantage. Having previously always campaigned on an anti-incumbent platform, Odinga is now running as the establishment candidate. But he is also looking elsewhere for support: he has attempted to forge a broad alliance by wooing major opposition figures, such as Kalonzo Musyoka, leader of the Wiper Democratic Movement, and Gideon Moi of the Kenya African National Union. The veteran leader’s camp is quietly confident. Their mood was boosted in mid-May after Odinga picked his running mate – who, as noted above, is Martha Karua, a highly regarded former minister from Central Kenya.

They hope she might woo some Kikuyu into the Odinga fold while bringing along some undecided moderates. The optimism appears to go deeper than that, however. “Odinga knows how to win elections; he has a broad support base and now at least the State is not working to stop him”, Paul Mwangi, Odinga’s longtime legal adviser, told Crisis Group.

—This is an extract from the International Crisis Group report on August polls

TOMORROW: Why observers are looking at Kenya’s elections with anxiety and trepidation.