Why Kenyans don’t feel effects of strong shilling, low inflation

Despite the Kenya Kwanza administration’s pride in the recent stability of the Kenyan shilling, indicators reveal a more complex reality, even after the currency strengthened after the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) intervened.

The apex bank has implemented a series of monetary policy measures aimed at reducing the cost of living by making borrowing more affordable.

Between August 2024 and February 2025, the CBK lowered its benchmark lending rate from 12.75 per cent to 10.75 per cent, marking four consecutive rate cuts. Additionally, the Cash Reserve Ratio (CRR) was reduced from 4.25 per cent to 3.25 per cent, effectively releasing approximately Sh57 billion in liquidity for banks to extend as credit.

These measures are designed to encourage commercial banks to decrease their lending rates, thereby increasing access to credit. Increased access to credit is expected to boost economic activities, enhance production, and potentially lead to lower prices for goods and services, contributing to a reduced cost of living. Despite these efforts, the CBK has observed that lending rates have not declined significantly, prompting on-site inspections to ensure banks comply with the new policy measures.

By easing monetary policy and increasing liquidity in the financial system, the CBK aims to support economic growth and alleviate the financial burden on Kenyans, striving to make essential goods and services more affordable.

The shilling remained stable against major international and regional currencies, during the week ending February 21. It exchanged at Sh129.58 per dollar, compared to Sh129.21 per US dollar the week of February 13, having hit an all-time high of over 160 against the dollar in March 2024.

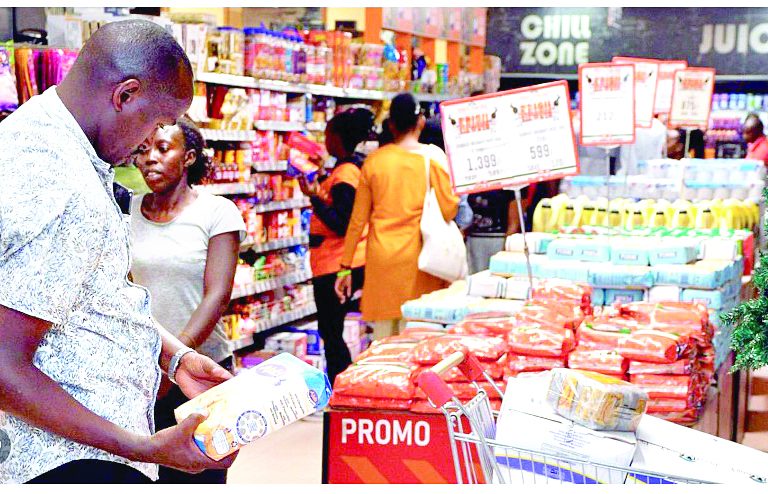

While the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) reports a decline in inflation to 3.3 per cent for January 2025, which is below its benchmark rate of 5 per cent, many Kenyans continue to grapple with high living costs and elevated food prices.

For instance, in February 2022, a 1kg packet of sugar was priced between Sh124 and Sh138, with the shilling trading at Sh120.54 to the dollar and an inflation rate of 5.08 per cent. Lower inflation rate As of January 2025, despite the shilling strengthening to approximately Sh129 against the dollar, the same packet of sugar averages Sh160 in major supermarkets. This price increase persists even as the CBK reports a lower inflation rate.

Similarly, other essential commodities have experienced price hikes over the past two years. In January 2023, the cost of a 2kg packet of maize flour was around Sh120. By January 2025, this price had risen to approximately Sh150, reflecting a significant increase despite the reported decline in inflation.

Speaking to Business Hub, Stacie Karegi, a Nairobi resident, complained of the current high food prices which have forced her to spend more for her household.

“Things are tough. the prices of products when you compare them with the previous year, they are increasing. For instance, last year in November we were getting a 2kg maize flour from as low as Sh120, for a good brand, now we are talking about Sh160 of the same. for a 5 litre cooking oil, it was retaining at about Sh1,100 during the same period, now I’m buying it from Sh1,500, the Ps statement is unrealistic,” she complained.

Violet Rudia, a casual labourer in Nairobi, agreed that the prices of commodities in the country have reduced compared to last year although remaining high compared to five years ago.\

“For now, I can say that on my end things have started becoming affordable for instance, you can get a Sh140 of maize flour, a 2 kg that is, compared to 2023 when they were at Sh210. This I think has also been influenced by the fertiliser subsidy initiative,” she said.

However, National Treasury Principal Secretary Chris Kiptoo argues that government interventions have alleviated the cost of living.

He states: “I’m happy because when I look back, so much has happened. I think I am right to say that the worst is over and the future is brighter. Inflation has come down not just because of CBK but also due to a combination of what we have done at the National Treasury.”

Economist Kwame Owino, however, offers a different perspective in his analysis of the economy. While he acknowledges the decline in inflation, he notes that it hasn’t translated into improved demand for goods and services.

Owino points out that while prices are decreasing slightly now, they had previously risen sharply over the past five years, outpacing income growth.

He remarks, “Over the past five years, if you look at the inflation basket, food inflation has really been hiking at a high rate. Irrespective of the fact that prices are dropping, they rose at higher levels than incomes.”

“If you measure the poverty levels today, Kenyans are poorer than they were in the year of Covid-19 and so if you take all those things together, Kenyans are not guessing, they say, fine you are giving us fine numbers but I cannot afford enough food. Poverty rate means that at 40 per cent, 21 million people do not have sufcient funds to feed themselves,” Owino added.

“What I must say is that Kenyans, we have serious work to do and we cannot wipe away this thing with flowery language and PR messages.”

The disparity between official inflation figures and the lived experiences of Kenyans can be attributed to several factors.

Inflation rates are calculated based on a basket of goods and services, and while some items may have stabilised or decreased in price, essential commodities like food have seen significant increases. Global events have also had a direct impact on local food prices in Kenya, contributing to the disconnect between reported inflation rates and the actual cost of living.

While the shilling has shown stability, the benefits of a stronger currency have not necessarily trickled down to consumers. Importers may still be dealing with higher costs from previous periods of currency weakness, and these costs are often passed on to consumers.

Additionally, domestic factors such as taxation, production costs, and distribution inefficiencies continue to influence retail prices.