Can mandatory vaccination be enforced in Kenya?

Desmond Odhiambo

The government recently expressed its aim to vaccinate 10 million people by December 2021, and 26 million by the end of 2022.

As part of efforts to achieve this ambition, it announced in early August that all civil servants must take the vaccine or face disciplinary action.

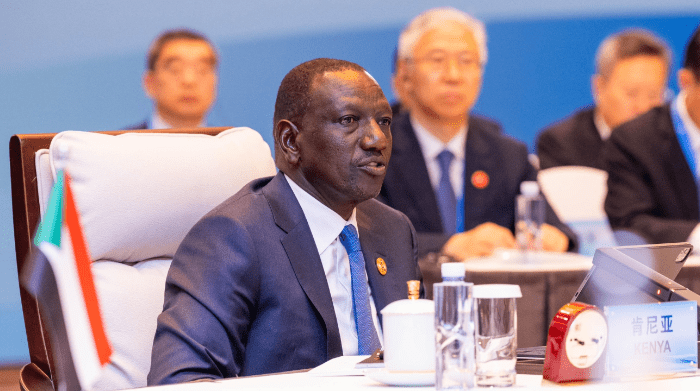

It was a decision that sparked public debate, forcing the President to clarify that there would be no mandatory vaccination but urged those in essential services to take the vaccine.

This brings questions to the fore, many of them relating to legislation. It would seem that there are two opposing opinions, each founded in legitimate law.

The first is that civil servants who do not get vaccinated disregard the shared responsibility to ensure their own health and safety while at the workplace.

Proponents of this sentiment point to The Occupational Safety and Health Act of 2007.

In contrast, the outcry against the directive was rooted in the fact that mandatory vaccination violated the constitutional right to “freedom of conscience, religion, thought, belief and opinion.”

There are a few considerations to be made when considering this matter. The first is that the decision to make vaccinations for civil servants mandatory was in the form of a confidential circular issued to members of the public service.

The decision was in no way ratified or put forward as a policy. It was no more than a managerial directive.

For now, civil servants can be encouraged to get vaccinated but mandatory policy to this end simply does not exist. Ratifying such policy would be a lengthy and hotly contested issue.

The directive, however, has provided ground for interesting debate and discussion on issues around human rights.

Are such directives necessary? Many would argue in the affirmative, given that, like other African nations, Kenya is experiencing vaccine hesitancy in certain quarters.

And here again, there are considerations to be made. The impact of fake news, for example, around the legitimacy of the virus and the alleged side-effects of the vaccine, cannot be underestimated.

The government has taken steps to curb the panic caused by fake news, but at this point, the steps amount to little more than damage control.

There is also a religious component to be considered. The hesitancy of some Kenyans to take the vaccine is based on religious grounds and we cannot infringe on the freedom of religion.

Another consideration to be made is that we are navigating uncharted territory.

Currently, certain vaccinations for children are mandatory. But this does not equate to precedent.

US precedent in the form of compulsory immunizations against the smallpox pandemic was set in 1905. But that’s as far as precedent extends.

There is no precedent for vaccinating people in the workplace for health and safety reasons.

Undoubtedly, employers in certain sectors are keen to reinstate working in-office, and so the private sector will take its lead from the public sector.

Corporate Kenya will look to government for guidance on this matter.

What might be on the horizon are mandates for employees in vital sectors to receive vaccinations.

For example, healthcare workers could in future be required to be vaccinated to curb infections.

The hospitality industry has been brought to a standstill by the pandemic and vaccination of employees could change the situation.

There is also the possibility of discrimination within the workplace based on whether employees have been vaccinated.

Hiring based on one’s vaccination status would be considered discrimination and a violation of fundamental rights as outlined in the Constitution. —The writer is an Advocate of the High Court of Kenya