Covid-19 pandemic ticking time bomb in Kenyan slums

The Health ministry’s warning that Kibera slum in Nairobi is emerging as a coronavirus hotspot has shifted focus to concerns that informal settlements are the weakest link in efforts to tame the deadly disease.

Because of their unplanned nature, informal settlements are filthy, crowded, lack basic amenities and proper housing; they are a ticking time bomb.

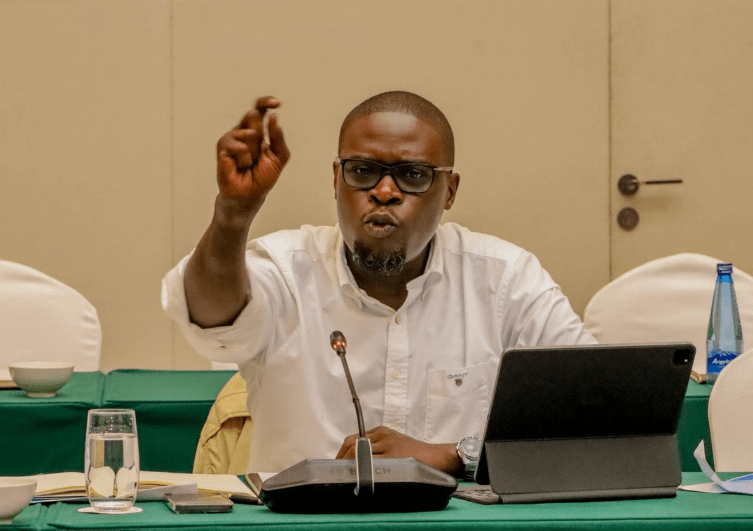

Yesterday, Health Cabinet Secretary Mutahi Kagwe moved to address this concern as the number of infections in the country rose to 225 after nine more positive cases were confirmed.

Addressing the press during his daily updates on the Covid-19, he said health officials were on the ground in Kibera to conduct mass testing.

“We have started surveillance work and our team is already on the ground in Kibera. We are trying to see whether there is any cause for concern,” he said.

On Tuesday, Health Chief Administrative Secretary Mercy Mwangangi had said the government would carry out mass testing in Nairobi, targeting the informal settlement because it is among the six high-risk areas in the country.

The other counties are Mandera, Kiambu, Machakos, Kilifi and Mombasa.

Complicate matters

A survey by the People Daily in Nairobi, Kisumu, Nakuru and Mombasa found that informal settlements could indeed be a festering ground for the deadly respiratory flu.

The fact that the slums share similar characteristics such as high population density, lack of basic amenities, unsanitary conditions and numerous illicit brew dens that operate even during curfew hours and a shared belief that “the disease is for the rich” could present the weakest link in the war against coronavirus in Kenya.

The slums are near impossible to call to order because the residents— “the wretched of the cities”— who are of diverse demographic and cultural mix, are caught up in a cruel web of socio-economic challenges that render them to the fringes of survival.

In Kibera, for instance, some of residents interviewed said their biggest fear at the moment is going to bed hungry, not contracting the disease.

A boda boda operator, who only identified himself as Ralph, said his biggest concern is that the curfew has complicated an already bad situation.

“We are people who struggle everyday, so this curfew has messed us up. Some officers are taking advantage of the situation to extort people and harass us and it is unfair.

On average, I make Sh1,000 ferrying goods for traders, but that is now diminished.

Government should review the timelines and maybe push the curfew times to weekends…” he said.

In Ayany area within the slum, a stall owner Nyar-Gem said: “I do not know what will happen in the coming days because times have become tough over here.

Look at my stock; it is diminishing and it is because those who bring us supplies are restricted in movement.

At the same time, people want (to shop on )credit because there is no money so it is crazy. This curfew is making matters complicated for us people in jua kali business,” she said.

Keep distance

Linet Kung’a, a mother of five who lives in Manyatta slums in Kisumu and makes a living making clothes, says although she is afraid of the disease, she cannot obey some of the government rules such as working from home and social distancing because she has to feed her children.

“If the virus gets here we will have no defence because the place is crowded.

Not everyone is using the sanitisers in front of shops and markets and only a few are following health guidelines on sneezing and coughing. Our fate is in God’s hands,” she added.

But with the spread of coronavirus fast moving to community transmission, medical and social experts are raising the red flag over of the fate of more than 10 million Kenyans living in urban slums should the pandemic get worse.

“Let us pray that the disease does not reach dangerous levels like (it has) in the US, Italy, Spain and China, otherwise the situation in our slums is simply a disaster in waiting,” says Dr Nichodemus Nyandiko, a disaster management lecturer at the Masinde Muliro University.

According to Nyandiko, expansive and densely-populated slums, including Kibera in Nairobi, Bangladesh in Mombasa and Kondele in Kisumu, could become hotbeds for the Covid-19 pandemic.

His sentiments are shared by Mairura Omwenga, the chairman of Town and County Planners Association of Kenya, who says unplanned human settlements are usually exposed to fast spread of diseases.

Omwenga, an engineer and urban planner, says slums provide a conducive environment for viral diseases to spread.

Another urban planner, Moses Orege, says residents in informal settlements are prone to infectious diseases because of crowding and poor sanitary conditions.

“The congestion in informal settlements may fan the spread of diseases as has been seen with infectious diseases such as cholera,” he says.

The crowding in informal settlements makes adhering to protective measures such as social distancing difficult.

“One cannot imagine keeping physical and social distance in a 10ft-by-10ft house for a family of five or more.

To make it worse, this 10ft-by-10ft residential space is attached at the back and sides to similar houses with almost similar population size. It is untenable to adhere to some of these Covid-19 health guidelines,” says Orege.

Dr Mazaher Jaffer, a lecturer at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and the head of Infectious Diseases Clinic at MP Shah Hospital, said evidence from past crises shows that though not everyone is affected equally; the most vulnerable people invariably suffer the worst.

“This threat will strike worst at the 10 million-or-so people living in the thousands of dense informal settlements, or slums, that pack most the major towns in Kenya,” he says.