Hot on the heels of the heated talks on climate finance at COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan, another row has erupted over global heating at the third consecutive world climate meeting, which opened on Monday in Busan, South Korea.

This time around the wrangles that rocked the opening session of the United Nations Plastics Negotiations in Busan were a spill-over from COP29 and revolved around the contentious issue of fossil fuels- an issue that remained unresolved in Baku.

While the negotiations on the main agenda in Baku – climate finance – were fractious, discussions on fossil fuels in Busan were equally grumpy from the onset of the negotiations.

“Oil-rich Saudi Arabia did its utmost throughout the climate summit in Baku to obstruct mentions of the globally-agreed transition away from fossil fuels, as well as human rights, across all texts,” reported the authoritative UK-based Climate Home News, adding that these efforts to upend the COP28 consensus on energy transition meant that negotiations had to be moved to next year.

The climate summit were acrimonious as disgruntled developing nations complained over the $300 billion a year in climate finance deal struck instead of the $1.3 trillion dollars they wanted to cope with the heavy burden of global warming caused by big emitters from wealthy nations.

The fallout in Baku, which has now spilled over to the Busan negotiations for a Global Plastics Treaty means that all the three crucial UN meetings on the three main issues confronting humanity and the planet– climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution – have been rocked by controversy and deadlock.

The UN Convention on Biodiversity (COP16) or the ‘People’s COP’ last month in Cali, Colombia, brought diverse voices to the table and highlighted growing urgency around the biodiversity crisis, progress on its core objectives came up short.

Negotiators faced gridlock over key finance decisions (just as in Baku) and many countries showed lagging ambition. The summit ultimately ended without agreement on a range of issues – most importantly how to finance conservation at the scale needed.

Still COP16 in Colombia offered a pulse check on the world’s biodiversity efforts to date. It revealed how far the world has come toward its collective targets and what exactly needs to be done this decade to safeguard Mother Earth’s precious remaining species, according to the World Resources Institute.

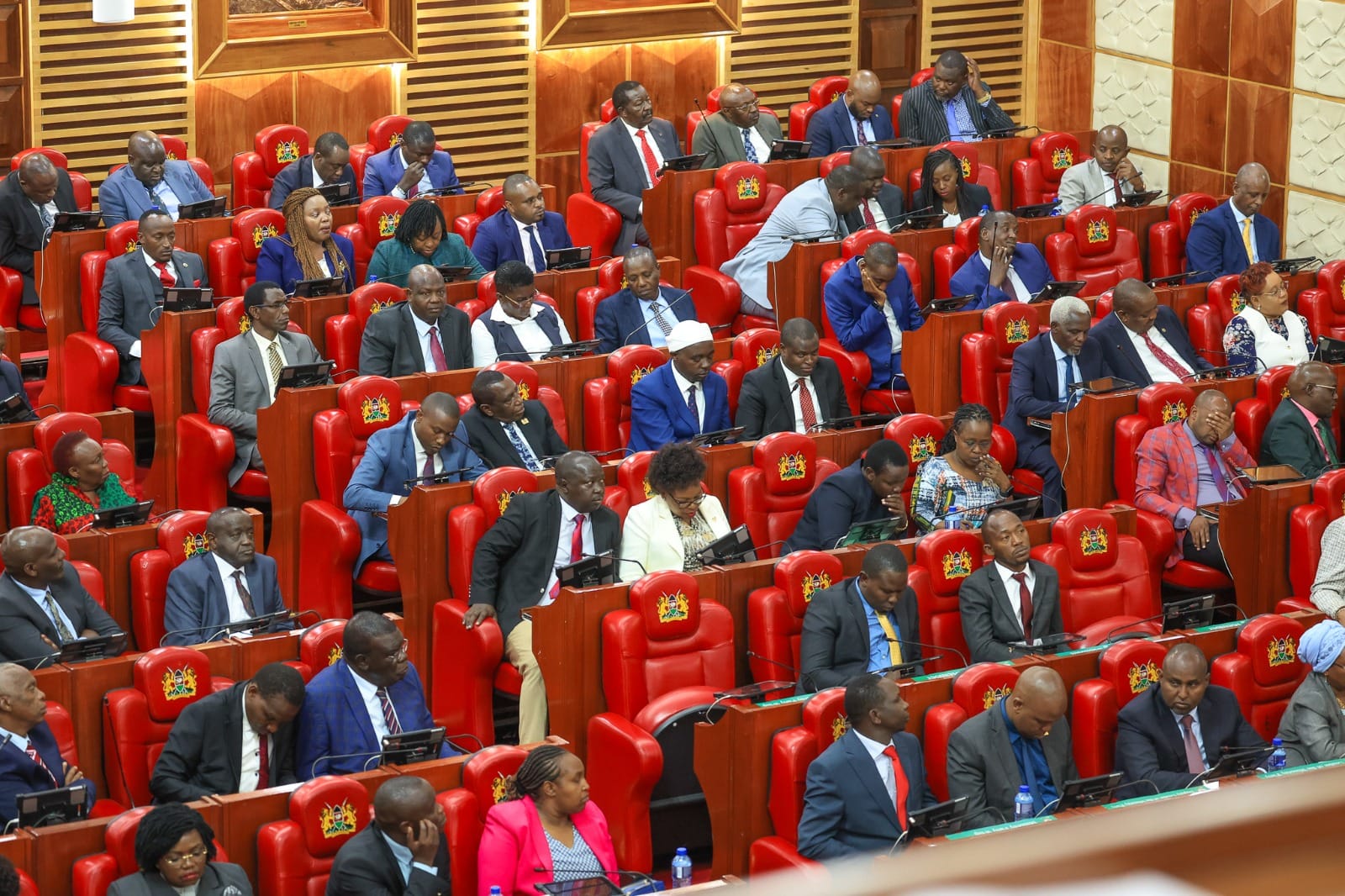

Fast forward to Busan, South Korea’s second largest city after Seoul. Delegates from more than 175 countries are gathered for the last global environmental summit of the year that could place limits on fossil fuel production – this time with a new UN treaty on plastic pollution.

Negotiations started since late October to hammer out the details of a new treaty aimed at reducing pollution from plastic waste.

Divisions emerged on the first day in Busan, as countries picked up a now-common fight, forcing the opening plenary into overtime to resolve thorny procedural issues. Some fossil-fuel-producing nations like Iran, Russia and Saudi Arabia have fiercely opposed putting any limits on plastic production, almost all of which is derived from oil and gas.

Clear pathways

Ahead of the United Nations Plastic Negotiations in Busan, a new scientific study revealed that just four global policies could eliminate more than 90 per cent of plastic waste and 30 per cent of linked carbon emissions by 2050.

The study, ‘Pathways to Reduce Global Plastic Waste Management and Greenhouse Gas Emissions By 2050’, determined that just four policies can reduce mismanaged plastic waste, to mean plastic that isn’t recycled or properly disposed of and ends up as pollution, by 91 per cent and plastic-related greenhouse gases by one-third.

The comprehensive new study conducted by researchers at the University of California Berkeley and the University of California Santa Barbara released in the Science journal on November 14 2024, reveals that an ambitious treaty can nearly eliminate plastic pollution – a threat to people, wildlife and the climate.

The policies to tackle the global plastics menace identified in the study are diverse and include mandating new products be made with 40 per cent post-consumer recycled plastic, capping new plastic production at 2020 levels, investing significantly in waste management and implementing a token fee on plastic packaging.

Close relationship

In November last year, the Inter-governmental Negotiating Committee to Develop an Internationally Binding Instrument on Plastic Pollution, Including in the Marine Environment, met at the UNEP headquarters in Nairobi.

The fruits of this intergovernmental committee’s work on primary plastic polymers and chemicals and polymers of concern, waste management, existing plastic pollution and just transition could be finally realised with the signing of a Global Plastics Treaty.

A new global instrument will address the growing urgency to stem the critical issue of the trans-boundary tide of marine litter and plastic pollution. The systemic nature of the plastics problem requires cross-sector collaboration and interventions addressing the full lifecycle of plastics including production, consumption and disposal.

Oil spills are a testament to the devastating import that plastic has on the environment at every stage of its production, from when fossil fuel is extracted and transported to when plastic is irresponsibly disposed of.

The World Trade Organisation has highlighted the inextricable relationship between environment and economics. The trans-boundary nature of this challenge requires strategic international and national coordination to fill gaps in the existing framework of multilateral institutions through close collaboration with existing bodies and policies.

Finally, the new legal instrument negotiated for the Global Plastics Treaty ought to include language related to capacity building, technology transfer and financial assistance for developing countries in the efforts to achieve a plastic-free Africa.