Slave trade: International Day for the Remembrance of the Slave Trade

Listening to the lyrics of the classic song Shimoni by internationally acclaimed Kenyan-born British balladeer Roger Whittaker only strums your emotional heartstrings from beginning to end.

The four minutes and nine seconds-song leaves you with rage at the viciousness, torture and humiliation Africans endured during the Arab slave trade at the Kenyan coast and in Zanzibar.

It was inside the historic Shimoni caves in Kwale county, where Whittaker is said to have “heard voices” of slaves telling a tale of misery.

Nestled about 80km south of Mombasa, the gaping coral holes are reminiscence of nothing but blood, sweat and tears of Africans hunted by Omani Arabs, brutalised and captured, before lumped in the caves awaiting transportation to the slave market in Zanzibar.

Two theories explain the caves’ discovery: first, natives escaping slavery in Tanzania and Zanzibar discovered the caves and used them as hideout from hostile tribes. The second theory suggests the caves were discovered by Kifundi community, an offspring of the Persian community (locally known as Shirazi) and local Digo communities.

The Kifundi, who still exist today, are spread across Mkwiro, Shirazi, Bodo, and Funzi areas, also used the caves as hideouts. They named them Kaoni– Kifundi for ‘they can’t see’.

Superior arms

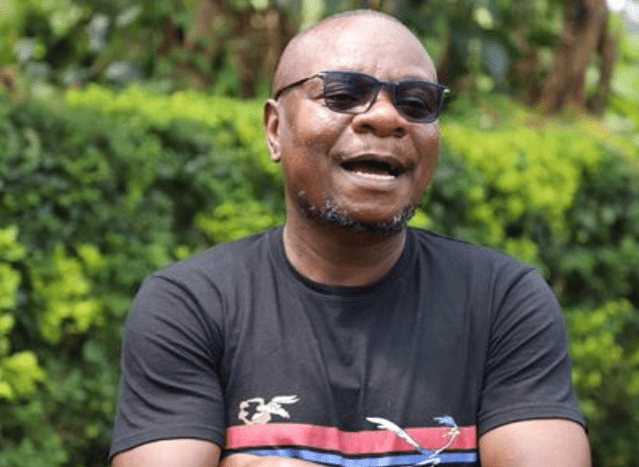

Dark, moist and stuffy, the caves have two tunnels: one leading to the mainland and the second stretching underground to the Indian Ocean. As Athman Ng’onga, a tour guide, explains, it is here where 1,000 slaves would be collected, forced to endure heat, suffocation and ocean water.

“On their arrival in East Africa, the Arab slave traders established a slave market in Zanzibar Island. They brought in Sultans of Oman to control it. These caves were a collection point for slaves,” says Ng’onga.

Armed with guns, the Arabs would go hunting for slaves in nearby villages and the hinterland. Through scheming and coordination with slavers, local paramount chiefs would trigger cattle rustling and war to capture prisoners, who were hounded away via caravan routes into the caves. Spears and machetes used by locals proved useless against guns the slavers brandished.

Captives stayed at the caves for three to four weeks, waiting for their numbers to get to the intended target of 1,000 before exiting through the underground tunnel onto awaiting vessel headed for Zanzibar.

“This entrance you see here today has a staircase; back then, there was nothing of the sort. It was a slanting cliff, with slaves first loaded with heavy luggage then pushed in. The weight meant their entry would be quick,” he says.

While waiting for shipment, captives experienced nothing short of absolute torture and humiliation. Sustained echoes of whip cracks coupled with loud screams were the order of the day, as evidenced by the remaining pieces of rusty metallic chains and hooks used to tie slaves during whipping.

On one side of the walls is a carved out chamber, elevated about one metre off the ground. It was a watchtower from where a muscular hawk-eyed armed Arab guard is said to have kept watch and averted any escape.

“Anyone who dared to escape was either gunned down instantly or tied facing the walls with his arms and legs spread widely open, then mercilessly whipped using a stick made from tamarind tree,” the guide explains.

Hunger and thirst

Just below the watchtower is a piece of coral rock protruding from the wall. It was specially designed for the punisher to rest and regain energy before he continues with the whipping.

“The caning would go on until the punisher got exhausted. The whipping was done as other slaves watched to instil fear. At times, slaves would be whipped continuously just to assess their level of resilience and strength. Many died in the process,” Ng’onga says.

During the month-long stay, captives were not allowed to eat or drink. They were only provided with dates from Oman.

“Dates have high sugar content and makes one thirsty, yet they were never given water. Instead, they were forced to drill a two-feet deep well on a coral surface from where they could drink salty water. Later on, the well, which sits below a gaping hole from the roof, was used to trap rainwater. That’s how those who were lucky survived,” the guide adds.

During high tide, water from the ocean seeped into the caves, and with nowhere to run, occupants had to endure the rising water levels, sometimes up to the waist level.

African traditionalists

The assortment of brutality, congestion and starvation sprouted diseases and even death. Surviving slaves were ordered to dump bodies in the ocean. Many others died on the long treks to the caves and others en route to Zanzibar .

“Bodies of those who died on caravan routes were abandoned on the way and those who died on ships were dumped in the ocean,” Ng’onga adds. Natives dreaded areas around the caves like leprosy for fear of falling prey.

The arrival of the British in East Africa around 1822 was seen as light at the end of the tunnel. They signed a series of treaties with Sultan Said Seyyid of Zanzibar to end slave trade. It would take 54 and 75 years for the trade to end along the Kenyan coast and in Zanzibar respectively.

Eventually, locals established settlements near the caves and converted them into shrines. “African traditionalists consider this cave holy and normally visit in calamity or drought to pray,” Ng’onga concludes.