In Kenya, the youth protests against planned tax increases have served as a wake-up call for the Church.

They’ve shaken up a powerful institution, in a country where more than 80 per cent of the population, including the president, are Christian.

The young demonstrators accused the Church of siding with the government, and took action against politicians using the pulpit as a political platform.

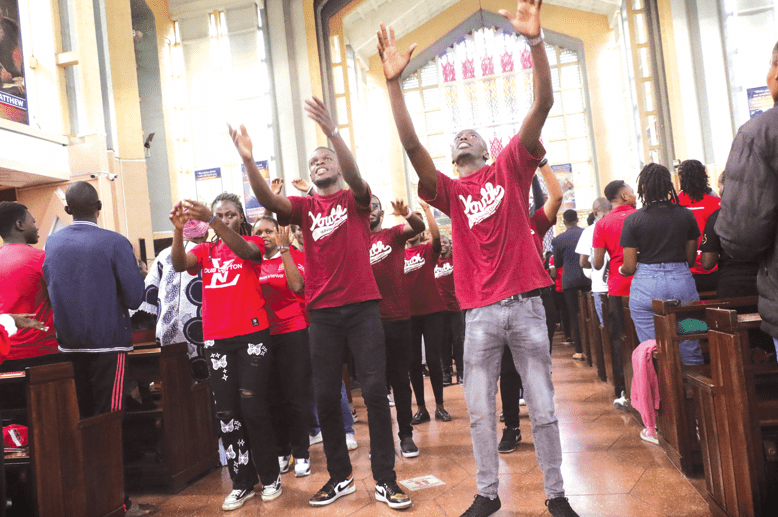

On a recent Sunday afternoon, Catholic leaders responded to the challenge.

They organised a special Mass for the youth from churches in and around Nairobi, to honour those who’d been killed by police in the anti-tax protests.

Hundreds of young people crowded into the Holy Family Basilica to pray for the dead.

Just weeks earlier, Sunday Mass had been interrupted by chants from the altar of the basilica.

It was an unprecedented protest from young people – the digitally savvy generation known as Generation Z or Gen-Z.

They felt the church wasn’t backing their campaign against tough tax hikes.

Now, Bishop Simon Kamomoe tried to convince them they’d been heard.

“I know as young people sometimes you feel disappointed even in the Church,” he said.

“We would like to renew our commitment in serving you. We can be mistaken…May the Lord forgive us as a Church, where even before God, we have disappointed you.”

He also admonished them to be patient in pursuit of their dreams, to be guided by the Church, and to repent of any sins committed during the protests.

Remarkable candour

“We don’t want to lose you, we don’t want to lose our young people,” he said, with remarkable candour. “The Catholic bishops are so concerned about losing this generation,” he said, urging them to stay peaceful and protect their lives.

The Mass was punctuated by spirited singing and ended with boisterous cheering as people waved Kenyan flags.

Several who attended said the service was a welcome first step, but a belated one.

“I feel like for the first time, the Church is realising that the young people are serious,” said Yebo, who attended the protests before they turned violent and wanted to remain anonymous.

“And I feel also the Church hasn’t been really on our side. They have been sitting on the fence for a long time.

“The youth have actually been more persistent, they have brought results more than the Church with the current economic change. We can hear the president is taking the youth more serious than he takes the Church serious.”

Church organisations did lobby against the tax bill, but it was young people taking to the streets in overwhelming numbers that forced President William Ruto to back down.

Not only that.

The Gen-Z protesters are now condemning what they see as the cozy relationship between Christian and political institutions.

Again and again on the side-lines of the Mass, they mentioned suspicions about visits by Church leaders to the State House, the presidential residence, including during the protests.

“We believe the president is buying the Church,” said Meshack Mwendwa.

On social media “the Church leaders are seen holding envelopes (alongside) the executive leaders and the permanent members of the government,” he said. “And that’s not what we want as the youth, now it’s time for a change.”

One change they demanded, and got, was an end to the ostentatious practice of “harambee” – politicians giving large sums of money to the Church.

Such donations can buy political influence on Sunday mornings.

The protest movement aimed to stop that – they called it #OccupyChurch.

Some even demonstrated against President Ruto’s attendance at a Church-sponsored event. But he supported their position.

“On matters of politics on the pulpit I am 100 per cent aligned,” he told a media roundtable that aired nationally.

Prosecute politics

“We shouldn’t be using the pulpit in churches or in any other places of worship, to prosecute politics. It is not right.”

Several days later, he banned state officers and public servants from making public charitable donations, and directed the attorney general to develop a mechanism for structured and transparent contributions.

But the president himself has been part of this political culture, converting the pulpit into a campaign platform.

“His political message was actually driven within the Church,” says Reverend Chris Kinyanjui, the general secretary of Kenya’s National Council of Churches (NCCK).

“So, people feel that they have a Christian government.”

Ruto’s Christian narrative has made it difficult for many pastors to hold him to account, Rev Kinyanjui said. Rather they behave like “shareholders of this administration,” he claimed.

“Our president speaks from the pulpit. You know what the pulpit means? He cannot be questioned. So, he has become a very powerful figure in Kenya’s politics and church circles. The Gen-Z are questioning, and are saying, we don’t know the difference between the government and the Church.”

Security services

The BBC asked the government for a response but the spokesman said he was unable to comment right now. He was speaking amidst sweeping changes in the cabinet and security services made by Ruto in response to the protests.

The backlash from Kenya’s young people has the potential to reshape the way power works in Kenya.

They make up the vast majority of the population, and are outside predictable political dynamics.

The president is listening now, and so is the Church.

“We are the Church,” said Mitchelee Mbugua outside the basilica as the Mass wound up.

“If the Church shows that they don’t support us, we draw away from them. If there are no us, there’s not a Church. So, they have to listen to our grievances. Because we are the Church.”

Rev Kinyanjui goes further, underlining what he sees as the fragility of the social contract with Kenya’s youth. He acknowledged that NCCK leadership had been worried that Kenya might go the way of Sudan.

There, a youth revolution was aborted by a military coup, which eventually led to civil war.

“We were happy that the president was able to defuse [this crisis],” he said, “because if he had signed that finance bill into law, who knows what we’d have become.”

Rev Kinyanjui said the NCCK came out “too quietly” against the finance bill. Going forward they will adopt a strategy of “being proactive, being visible, being the voice of and the consciousness of society… by questioning, by correcting the regime.”

“In a way, we see the Gen-Z as doing the Lord’s work, and I think that’s something that has made many pastors to wake up.”