Kenya’s energy sector is rapidly evolving as the government works to balance its goals for renewable energy growth with the challenges of managing excess capacity. In recent years, foreign investment in the energy market has surged, leading to concerns of oversupply that could spike electricity prices due to the costs of idle capacity.

To address these risks, the Kenyan government is considering a more selective approach to accepting energy generation proposals from foreign investors, aiming for a supply-demand equilibrium.

One solution being explored is a demand forecasting model to carefully regulate the entry of new energy projects. This tool would enable the government to stagger new projects over an extended timeline, potentially stretching implementation until 2043.

By pacing the development of energy infrastructure, the government hopes to avoid a sudden influx of energy that could destabilize the market and lead to higher tariffs. This approach aligns with Kenya’s commitment to achieving 100 per cent renewable energy by 2030—a goal that, while ambitious, must be approached without compromising affordability for consumers.

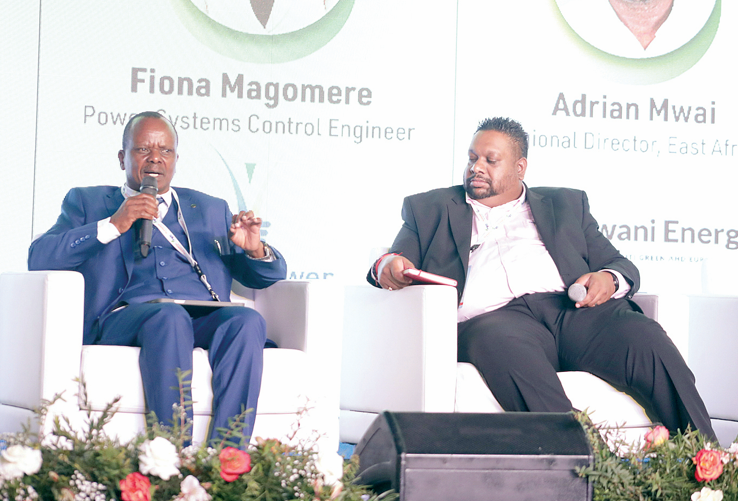

Benson Mwakina, Director of Renewable Energy at the Ministry of Energy and Petroleum, yesterday reiterated the importance of a measured approach. “We cannot afford to have one source beyond what we can sustain,” he explained. “A surplus in generation leads to higher electricity costs, so we must balance what we’re bringing in with what we’re distributing.”

Mwakina’s comments, made at a solar energy conference in Nairobi, signals the strategic caution with which Kenya is approaching its renewable energy expansion.

Kenya’s energy mix has seen substantial diversification over the past decade, with contributions from hydro, geothermal, wind, and solar power sources. Geothermal energy alone accounts for almost 50 per cent of the nation’s energy production, making Kenya one of the world’s leaders in geothermal utilisation. The total installed capacity for grid-connected electricity is approximately 2,990 MW—a figure that reflects both the country’s growing energy needs and its commitment to sustainable sources.

However, meeting these needs without driving up consumer costs is a complex challenge. Currently, residential electricity tariffs range from Sh12.23 per kWh for the lowest usage bracket to Sh19.08 per kWh for those consuming more than 100 kWh per month. Small businesses face similar tiered rates, with the highest rate at Sh16.34 per kWh for medium-level usage. In addition, a Time of Use (TOU) tariff offers off-peak rates as low as Sh9.70 per kWh for small commercial consumers, encouraging energy use during less congested times.

These tariffs reflect an attempt to keep energy costs manageable while also responding to public concerns over high electricity bills.

The risk of oversupply brings additional complexities. According to Mwakina, if too many generation projects are approved simultaneously, the resulting surplus can lead to a decrease in electricity prices that might seem beneficial initially but could fail to cover operational costs in the long term.

Such a scenario often forces utility providers to raise tariffs to recoup losses, passing higher costs to consumers. This situation underscores the importance of aligning project approvals with demand forecasts to maintain stability in energy pricing.

“When planning for the short, medium, and long term, we must consider which projects to accommodate and when based on demand projections,” Mwakina noted. “Expressions of interest come from solar, wind, small hydro, and geothermal sources. Our objective is to maintain an adequate power mix at all times.”

To enhance the country’s energy infrastructure, the government recently awarded a $736 million (Sh95 billion) contract to Indian business mogul Gautam Adani. This 30-year public-private partnership will see Adani manage key power transmission lines and substations, tackling one of the country’s most pressing issues: frequent power outages. While Adani’s involvement is expected to bolster the national grid by adding 276 kilometres of high-voltage transmission lines, including routes like the 400-kV Gilgil-Thika-Malaa-Konza line, the deal has been a subject of concern in the country as people raised issues about public participation in the project. The project is set to conclude in 24 months, after which Adani will continue managing the infrastructure before transferring it to the Kenya Electricity Transmission Company (KETRACO).

By implementing a forecasting model and cautiously managing energy project approvals, the government hopes to avoid the pitfalls of oversupply and ensure a stable, sustainable, and accessible energy future for Kenyans.