Why I made my cancer struggles public

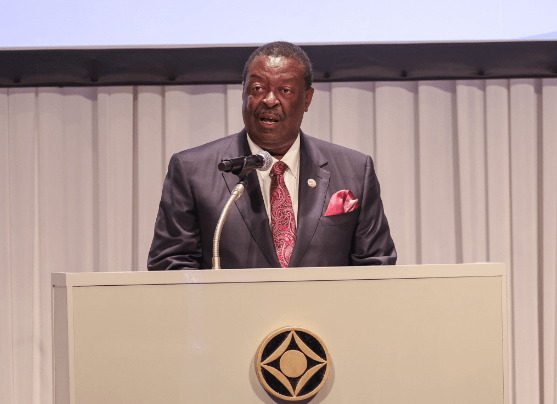

Living with liver cancer, OMONDI OCHUKA’s story is one of courage in adversity. He tells Harriet James

Not many people wish to make their worst moments in life a public spectacle. For some cancer patients, keeping the news of their diagnosis is a way of avoiding burdening friends and loved ones or alarming them.

For others, fear of judgment, of awkward conversations and sense of control over the situation pushes them to hide their condition.

But this was not the case for Omondi Ochuka, who was diagnosed with stage two inoperable primary liver cancer in 2011.

Instead of looking inwards and hiding away, he took to social media to show and illustrate the daily struggles he goes through as a cancer patient.

“I was writing a poem on my diary. It was around two in the afternoon. I had taken my pills; I remember counting them.

They were nine: big, small and in different colours. Then, I told myself I am going to show people these colours.

And then just posted it on Facebook,” begins Ochuka, who introduces himself as a soul, human thinker and cancer survivor.

Moment of release

That was back in 2014 and the poem, called Play Write, was one of the most vulnerable verses he had ever written— it was borne out of a conversation he had with his daughter Chieng Awuor, aged four then, about his diagnosis.

A photo of the medication he had just taken accompanied the poem. It was then that many of his friends and followers knew he had been suffering with liver cancer in silence.

“It was a moment of release for me and I never thought it would make such an impact. I am an introvert, but from that day I opted to show the world what was going on in my life as a result of cancer.

Many people commented experiencing shock on how close they were to me yet didn’t know I suffered from the disease.

They wondered how I had stood by myself without telling anyone what I was going through,” he explains.

This was the same spirit he had when it came to talking to his daughter about the progress of the disease.

“One time in 2015, we were in hospital and she asked me how I was feeling. That is one of the hardest questions I still find difficult to answer.

Breaking down cancer to my little girl was one of the heaviest moments in my life. I even thought that she’d come back and find me gone: that I might not be able to take care of her.

I kept telling her the one thing she should know is that I love her and that should carry her all her life,” explains the 30-year-old whose daughter lives with his late girlfriend’s sister in Stockholm, Sweden and visits Kenya every year.

Ochuka gets to bond with her during these visits, a moment he cherishes.

Talking about cancer is a subject that strikes fear into the hearts of most people and it’s a taboo disease most people, particularly men, shy from talking about.

A 2018 research in the UK indicated that over six million parents would delay telling children the cancer diagnosis of a loved one, with one in two people hiding it entirely. However, doctors caution against this secrecy.

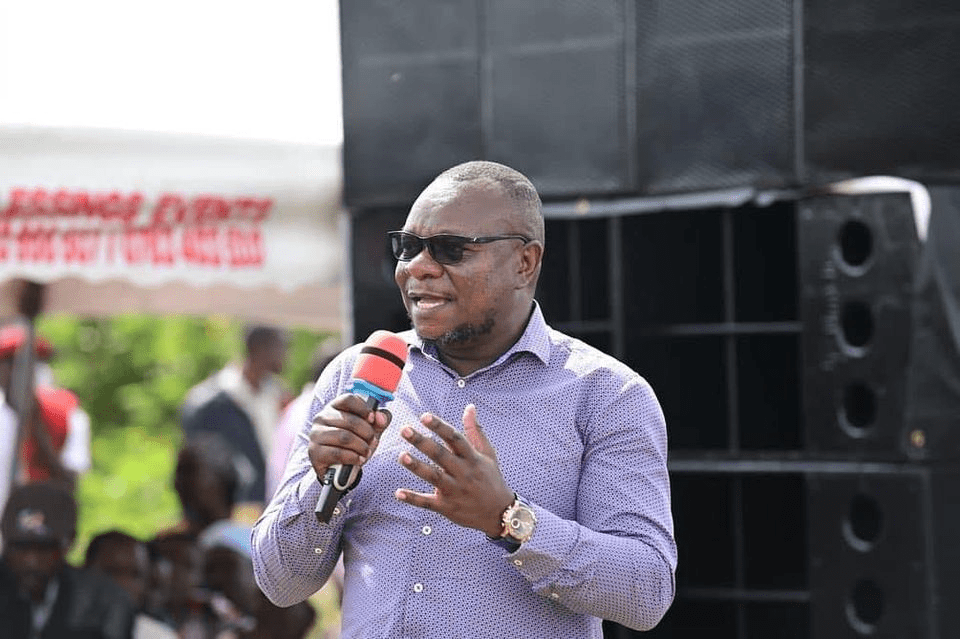

Dr Ian Kanyanya, a psychiatrist, says it is important to avail all the information to the patient and family.

“Let all the information concerning how far the malady is and what is ailing them and everything else they may want to know be availed. Know and understand what is happening.

Even the family may have questions. All the information should be provided and it helps them cope with the disease,” he said.

Treating cancer is not a walk in the park. “It is often expensive and costs an arm and a leg, but having a NHIF cover or insurance plans goes a long way.

It eases even the financial pressure, especially for parents who are sick. It eases the stress of them thinking about who will take care of their children and as such, the family comes in.

Family is what grounds patients, knowing that their children will still have persons to take care of them even as they battle the malady gives them the right state of mind,” Dr Catherine Nyongesa of Texas Cancer Centre says.

Experts have also indicated that despite the wide coverage of the disease on popular media, discussing cancer with family and friends is hard, but it is even harder when it comes to the general public, especially since many do not want to be treated differently from their pre-diagnosis days.

Ochuka’s opening up about his experiences through his writing, which contain a certain sting of darkness, enable him narrate that human side of cancer.

“It was therapeutic too because it was a way of talking to myself and finding out how my inner state was handling the whole experience.

I interacted with a lot of people going through depression or various sicknesses and those who are celebrating their wins.

This made me realise we are all made up of stories and there is no better way of connecting with people other than that.

Vulnerability is the first language of expression for me out there,” he adds.

Although Ochuka has always been drawn to art since his childhood, battling cancer pushed him to writing, a mode he uses to talk about the emotional, mental and financial pains he suffers as a cancer patient.

“I want to see how my pain looks like when I’m writing about it. But on the other hand, I want to see how strong I am as a person.

Being powerless and helpless is human. There are days I can lack, others I have, others I have joy, others sorrow,” he explains.

One greatest pain Ochuka goes through is the cost of his treatment.

“You need a lot of tests, scans, all the time. An X-ray at Kenyatta National Hospital (KNH) can cost Sh1,500. But what can an X-ray show you?

You need an MRI with very high resolution to show you deeper details such as the image of the tumour or why your body is not responding to treatment.

One radiotherapy session at KNH is Sh500 a session if you have National Hospital Insurance Fund (NHIF) cover.

If not, it costs Sh1,000. The session depends on the patient and the type and nature of cancer. A liver function test in Aga Khan costs Sh75,000 and in KNH, Sh40,000. How many people can afford to pay all that at once?

I have a lot of medicine that are so essential I can’t miss them. When they are about to finish, I get anxious because I have to look for money to get them. I tablet costs Sh65,000,” says Ochuka.

Another pain he experiences is drug side effects. For instance, epilem, a drug he takes for seizures, causes depression and his ability to control pee.

“It would make me feel off and bad. During such moments, I withdraw from people, which is not very healthy as there are times I need people.

I also break down when I need people and can’t find assistance. I feel helpless and want the pain to end,” he explains.

Support from friend and family is important as it helps patients navigate through life. They can be the link to pulling a patient from depression.

“It is best to get a psychiatrist to talk to and help the person get back to their normal selves. If they used to work or go to school, that should not stop.

Let them continue with their daily routines without making them feel in need of help every once in a while. Counsellors play a huge role when it comes to palliative care,” says Dr Nyongesa.

Life continues

These are sentiments Dr Kanyanya echoes. “Life goes on. Cancer is not a death sentence. Some are treatable and curable and so, normalcy is necessary.

Life does not stop and if indeed they have emotional and physical strength, they should go about their lives,” he says.

It is the kindness of strangers and the support group he has amassed over the years that keeps Ochuka going.

Friends who send financial contributions, who support his music and art and those who send encouraging messages are what keep his spirit strong and to keep him sane amidst all the suffering.

With all these behind him, one would think he doesn’t get negative comments or people. People have unfriended or even blocked him on social media because of what he shares.

Some, once close to him, have deserted him and others have given him empty promises.

“Sometimes, I imagine I am too much for people and some have even told me my wall is too sad.

I just smile; I am a very easy person and laid back and rarely hold grudges because that’s how they feel.

I also don’t try to justify myself or reduce how active I am on social media because of them,” he adds.