What Trump cut of WHO funding means for Kenya’s war on Corona

Clifford Akumu

Concern is mounting on the future of the management of infectious and non-infectious diseases in sub-Saharan Africa after United States President Donald Trump announced funding cut for the World Health Organisation amid the coronavirus pandemic.

Trump’s decision on Tuesday puts several WHO programmes, including emergency mitigation of the Covid-19, in danger of being set aside as hundreds of millions of dollars in funding dries up.

While announcing his decision, Trump accused the global health watchdog of promoting what he termed as “China’s disinformation about the virus’ that likely led to a wider outbreak globally, including his country.

But what could this announcement that has sent panic across the globe mean for developing countries grappling with weak health systems and infrastructure?

WHO is the leading United Nations body dealing with health issues across the globe including the deadly Covid-19.

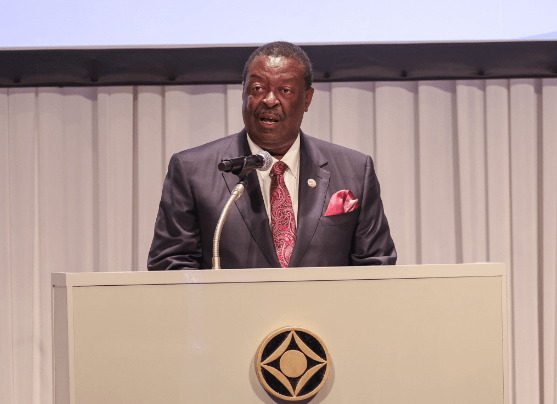

Prof Kenneth Ngure, a lecturer at the Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology’s School of Public Health, told People Daily that Trump’s decision to cut WHO funding “is bad news for global health programmes for sub-Saharan Africa countries including Kenya.”

Ripple effect

“As experts, we are crossing our fingers for a reconsideration of the decision,” said Ngure, who is also conducting research on the needs of adolescent girls and young women living with HIV/Aids.

Unlike other international organisations, WHO relies mostly on donor countries to function. Reducing funding will have a debilitating ripple effect across the country, added Ngure.

In 2020-21, WHO has allotted almost $4.8 billion (Sh480 billion) for its health programmes including fighting malaria, eradicating polio as well as special research and preparation for possible disease outbreaks.

Reacting to Trump’s decision, WHO Director General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus regretted the move but called on world unity to fight the new pandemic.

“We are assessing the impact and would try to fill any gaps with partners,” he said.

According to a UN report, as of March 2020 Trump’s administration also has an outstanding contribution of around $99 million (Sh9.9 billion) to the WHO from 2019 and the first three months of this year.

Ngure said WHO at this point will need to cast its net wider by looking at multilateral donors to help it set up funds to fill the gap.

“Making such an announcement in the middle of a pandemic is very unfortunate,” said Ngure in reference to the global COVID-19 that has infected more than two million people globally and killed more than 135,000.

The professor said this is the right time to increase funding for WHO to avoid future pandemics, adding: “The WHO has removed the veil on global health emergencies across the world.”

Trump’s announcement could mean that as much as $720 million (Sh72 billion) worth of WHO programmes could go unfunded this year and the next.

Most of Sub-Saharan governments gets health funding from donors and taxes. With this cut in funding, officials will need to go back to the drawing board to craft new funding strategies that could support the management of deadly diseases.

However, this could serve as a wake-up call for sub-Saharan African nations, experts and scientists in management of such infectious diseases should the Trump administration maintain its ground.

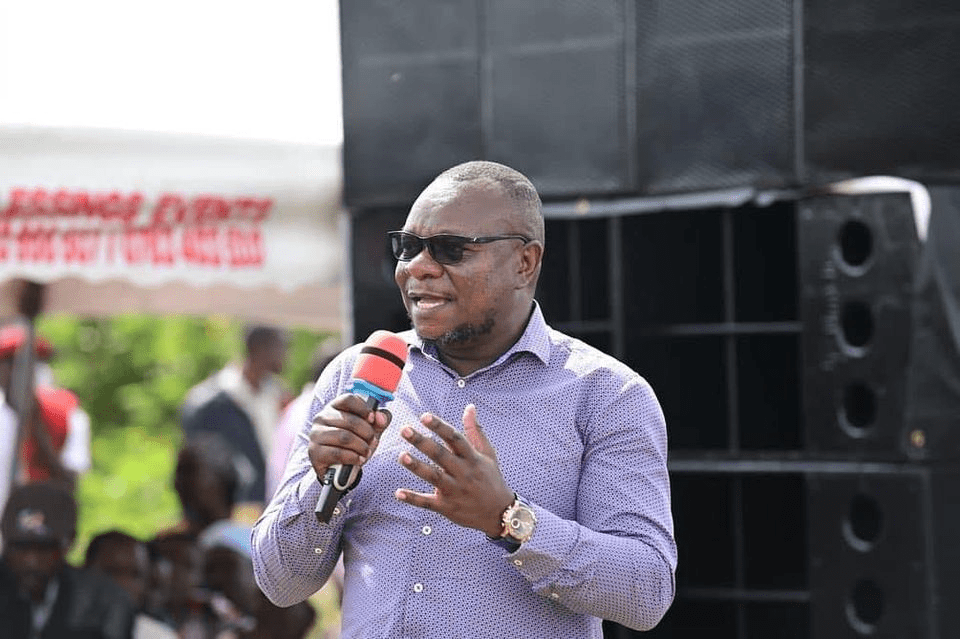

Dr Patrick Oyaro, an epidemiologists and the chief executive officer Health Innovation Kenya, believes formation of a strong scientific body akin to the WHO in Africa could be the answer to the infectious diseases’ puzzle.

What he termed as an “African Centre for Disease Control” would come up with strong strategies to manage some of the deadly infections.

“We already have expertise working within the WHO. It is just a matter of coming back home and building ‘Jerusalem,’” he added.

Oyaro said the withdrawal of US funding to WHO would lead to non-development, or delayed development, of guidelines on infectious diseases.

Political will

Sub-Saharan Africa and Asia have depended on WHO guidelines because it uses public health approach in modelling its management guidelines.

“We can custom-make some of the guidelines to suit specific country’s needs,” said Oyaro.

He, however, said that for such a scientific body to function, there is need for political will to strengthen its functions.

Oyaro further noted that before countries panic, there is need to revisit the US regulation and procedures that informed the pulling out of such funding.

“Does Trump have the backup of other organs in his administration tasked with making such approvals?” he posed.

The proportion of funding allocated by WHO to support third world countries in management of diseases will also come into play.. Other counties and super powers who contribute for WHO could come in cushion the UN body from the impact Trump’s decision.

“Other contributors like the EU, China among others might come in to fill the gap,” he said.

But other experts see this decision as a power struggle between the US and China spilling into the critical phase of a pandemic that is poised to affect other deadly diseases’ management.