Vice presidents who, like Ruto, defied bosses

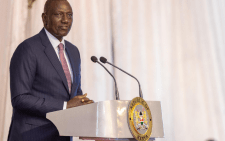

Outgoing Deputy President William Ruto has ruffled many feathers within and outside government.

While many find his style of politics unusual, he himself has identified nothing wrong with it, arguing that his critics have not proven any form of ineptitude or conduct unbecoming on his part.

What confounds both friend and foe are the alacrity, confidence, vigour and sheer stubbornness with which he confronts his political rivals. Even when engaged in a verbal exchange with President Uhuru Kenyatta and former Prime Minister Raila Odinga — his political seniors — Ruto pulls no punches.

His is a brand of internal political rebellion never witnessed before in independent Kenya since the 1960s when the founding president Jomo Kenyatta fell out with his first vice-president Jaramogi Oginga Odinga.

Notably, Uhuru is the son of the late Mzee Kenyatta, while Raila is Jaramogi’s son. The bite-and-blow relationship between Jomo and Jaramogi has rekindled itself in the Uhuru-Ruto tiff considering that their paerting of ways started to manifest publicly after the March 2018 “Handshake” between the President and Raila.

As late as a fortnight ago, only a week to the end of their Jubilee administration, there were no signs of closing of ranks between the President and his deputy, who became increasingly abrasive during the campaign period.

Whereas some Kenyans, including Azimio-One Kenya leaders like Martha Karua, have expressed discomfort at Ruto’s political tactics, his allies regard him as a committed house minder. Indeed, they believe he has been more sinned against than he has sinned.

From a historical perspective, Ruto is not the only deputy to have walked this treacherous avenue. Indeed, Africa continues to record not dissimilar confrontations between heads of State and their second-in-command.

In Botswana, a similar scenario unfolded in 2018. Ian Seretse Khama, who was retiring as president, tried to block his vice-president, Eric Mokweetsi Masisi, from ascending to the presidency. However, the attempt flopped after the latter outsmarted his boss, contested and won.

Similarly, late Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe was known to have had sharp differences with two of his vice-presidents, Dr Joyce Mujuru and Emerson Mnangagwa, who eventually succeeded him.

Mujuru was hounded out of office for alleged insubordination and use of witchcraft against her then elderly boss. Mnangagwa, on the other hand, was replaced while on a tour to South Africa but staged a successful military coup against Mugabe, who he then replaced in a bloodless transition.

Kagame and Bizimungu

Relations were not any better for Paul Kagame of Rwanda when he served as Pasteur Bizimungu’s vice-president in the second half of the 1990s just as was the case with current South African President Cyril Ramaphosa when he deputised his predecessor, Jacob Zuma.

Further abroad, in Austria in 2020, Vice-Chancellor (equivalent of Deputy President) Heinz Christian-Strache had a frosty working relationship with his boss, Chancellor Sebastian Kurz. He was forced to resign after videos recorded two years earlier in Ibiza, Spain, emerged showing the then leader of the far-right Freedom Party in a rendezvous with a Russian sex hawker and other vendors of the vice discussing how to engage in corrupt deals worth billions of Euros.

Duterte and Robredo

The same applied to former President of Phillipines Rodrigo Duterte owho had no love lost with his principal assistant, Leni Robredo. Duterte criticised his deputy left, right and centre and accused her of undermining his administration. He appointed Robredo – a fierce critic of her boss – to spearheaded the anti-narcotics campaign in the country after she complained of the way in which suspects were being killed in total disregard of their human rights.

In elections held two months ago, Robredo lost the presidential contest to Ferdinand Marcos Jnr, the son of former despot Ferdinand Marcos.

In Venezuela, President Nicolas Maduro has had a tempestuous relationship with three successive vice-presidents Jorge Arreaza, Aristobulo Isturiz and Tareck El Aissami.

Similarly, former Malaysian Deputy Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim had a series of tiffs with his boss, Mahathir Mohammed, in the late 1990s and early 2000s to a level that saw him jailed over claims of corruption and sexual misconduct.

Former Italian Prime Minister Guissepe Conte and his then deputy, Matteo Salvini, also had a shaky working relationship that led to the breaking up of their ruling coalition and a snap election in which Salvini was edged out of the political centre-stage.

In all these cases, however, only Kagame, Ramaphosa and Mnangagwa surmounted the odds and went on to become Heads of State in their respective countries, a footnote that Ruto may want to take interest in.

Ruto might also be interested in the case of Jaramogi and Mzee Kenyatta, which remains a classic example for current and future politicians to learn from. Jaramogi ended up becoming the doyen of opposition politics after his fall-out with Jomo.

Young Turks

Though he was the country’s first vice-president, Jaramogiremained in the political cold for decades. From there, he vigorously, amid intermittent harassment and isolation by the State and its agencies, pushed for a return to multi-party politics, a feat he achieved much later in life, thanks to a coterie of youthful professionals who came to be known as “the Young Turks”.

Though he fought for the opening up of democratic space in Kenya, Jaramogi never ascended to the highest seat in the land. That hope now lies with his son, who was been endorsed by Uhuru, who happens to be Jomo’s son and Ruto’s boss.