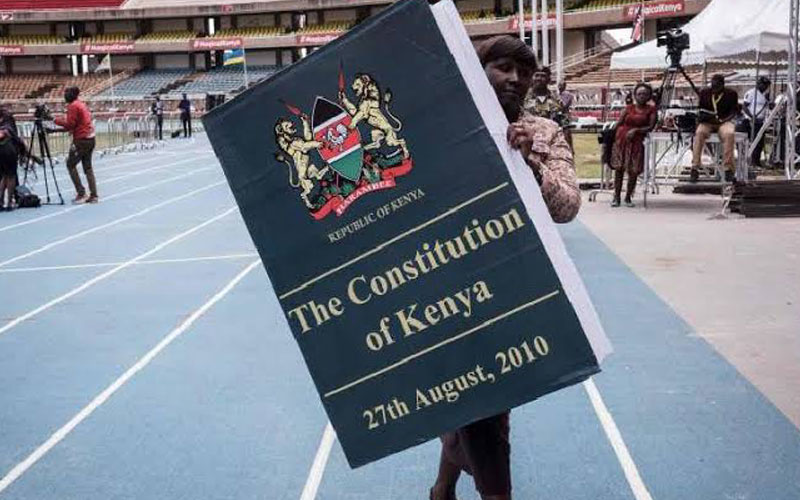

Naivasha: Where ineffective, weak Senate was born

Emeka-Mayaka Gekara

The country is marking a decade since enactment of the 2010 Constitution at a time when the Senate is the stage of an ugly battle over the sharing of revenue among counties.

The Senate, which is mandated to protect devolution, is one of the new creatures in the Constitution.

There was a Senate at independence but it was scrapped following a constitutional amendment. However, the current Senate has been criticised as weak and limited in oversight and legislation.

And the buck has been placed at on the Parliamentary Committee on the Constitution which tinkered with the Harmonised Draft which had been put together by the Committee of Experts (CoE) and which had proposed a powerful Senate with a supervisory role over the National Assembly.

Through a twist of fate, some of the members of the committee that was chaired by former Mandera Central Member of Parliament Abdikadir Mohammed, who are blamed for weakening the institution, ended up being elected to the Senate.

Notable members of the committee included President Uhuru Kenyatta, his deputy William Ruto, Amani National Congress chief Musalia Mudavadi, Narc-Kenya leader Martha Karua, Senators Amos Wako (then Attorney General), Moses Wetang’ula and James Orengo; Ndaragwa MP Jeremiah Kioni and Foreign Affairs Chief Administrative Secretary Ababu Namwamba, who was Mohammed’s deputy.

Others were Kitui Governor Charity Ngilu, Cabinet Secretaries Peter Munya and Najib Balala, former Cabinet minister Sally Kosgei, former Kitui Senator David Musila, Chama Cha Mashinani chief Isaac Ruto and Suba North MP Millie Odhiambo.

The committee in January 2010 spent a week in Naivasha to broker consensus on what had been identified as contentious issues.

While in Naivasha, Wetang’ula argued that creation of the Senate would be a burden on taxpayers.

“If the Senate comes, I personally do not want its membership to be more than 40,” he argued.

Kioni suggested that the roles assigned to the Senate under the 2010 Constitution could be undertaken by a committee of Parliament.

“What is it that Senate will be doing that cannot be done by a strong committee of Parliament?” asked Kioni, who after the passing of the Constitution, unsuccessfully launched an effort to scrap it.

On her part, Karua saw the Senate as a duplication while former Garsen MP Danson Mungatana proposed the creation of a special committee of Parliament on devolution instead of creating another chamber.

But Ruto made a strong argument for establishment of a Senate. He was of the view that the institution would be a strong check on presidents who are often keen to retain resources at the centre and frustrate devolution.

“Members have asked here; what is going to be the purpose of the Senate or the devolved units?” he posed.

“The tendency of a President like the one we have to centralise resources and government activity is very high and it is very necessary for us to adopt a devolved system that makes it mandatory, so that it is not the discretion of anybody.”

The Senate, Ruto argued, would give a sense of “equitability” in representation.

A section of governors have also expressed opinion that the responsibility of oversight of the sub-nationals falls under county assemblies and see the Senate as an irrelevant irritant and duplication.

Senior Counsel Nzamba Kitonga, who chaired the Committee of Experts that put together the 2010 Constitution, has described the weakening of the Senate as the “greatest tragedy” of the Naivasha talks.

The role of the Kitonga team was to piece together the various documents including the Bomas, Kilifi and Wako drafts to come up with the Harmonised Draft for transmission to the House team.

And the Abdikadir team was tasked to review the Harmonised Draft and come up with a consensus document that would then be subjected to a referendum.

Kitonga points fingers at the Naivasha committee, accusing it of weakening the structure of the Senate they had proposed in the Harmonised Draft.

“The greatest tragedy from Naivasha was the mutilation of the Senate. For the first time in the history of the architecture of constitutions in the world, a Senate was designated as a ‘lower house’.

This had never happened anywhere else in the world,” argues Kitonga.

The result of this was the twin rivalry after the 2013 election between the two Houses with members from both sides flexing their muscles to demonstrate that theirs was the more powerful and prestigious.

According to Kitonga, they had envisaged a powerful Senate with a supervisory role over the National Assembly.

However, the Naivasha team came up a peculiar structure of the Senate that rendered it the “lower” House with an oversight role over county governments without powers to review legislation from the National Assembly.

“Even during the Roman Empire, the Senate was designed as the ultimate stamp of the people’s authority.

The CoE had drafted a seamless legislative system where Bills and oversight reports would originate from the National Assembly and proceed to the Senate for approval, amendment or rejection.

The Bills would then proceed to the Presidency for assent,” he says.

But speaking to People Daily yesterday former MP Abdikadir defended the role of his team in the process, saying it had the delicate balancing act of reaching a compromise on the contentious issues in the face of entrenched positions by camps allied to President Mwai Kibaki’s Party of National Unity and Raila Odinga’s Orange Democratic Movement.

He pointed out that the composition of the 27-member House committee drawing members from both camps – including two deputy prime ministers (Uhuru and Mudavadi) – highlighted the high stakes in the process.

According to Abdikadir, the current structure of the Senate was a “negotiated political compromise” between the two camps.

“Members were strongly divided on the Senate. The ODM team was pushing for a powerful Senate while those from PNU did want creation of another chamber.

We had to reach a settlement otherwise the document would have been defeated at the referendum,” he said.

“PSC was the premier constitutional making body that was supposed to manage and run the process.

We are the ones who hired the experts. The Senate is not a product of Naivasha. It became a product of the people who ratified it during the referendum.”

Abdikadir also defended the team against the argument by Kitonga that they created a pure presidential system that was never in any of the drafts, saying it was another negotiated settlement.

“The negotiations touching on the structure of government was highly emotive. ODM wanted a parliamentary system while PNU wanted a hybrid system.

That is why we settled for the presidential system that was acceptable to both camps,” he said.

There have been consistent calls to scrap the Senate which some critics see as largely ineffective, parasitic, vindictive and expensive.

Former Pokot Governor Simon Kachapin feels that though critical, the current Senate is a threat to devolution which he sees as the only hope for communities that have suffered many years of neglect by national governments.

“The Senate is supposed to make laws that empower counties. But we have a weak, bitter and desperate Senate.

The Constitution is vague on oversight. We have a dangerous Senate,” he argues.

“Unless we amend the law to have a strong Senate, this one will never be effective. It should be dissolved,” he said in a past interview.

Makueni Governor Kivutha Kibwana offers that the 2010 Constitution can be reviewed to strengthen the Senate and reinforce devolution.

Kenya’s first Constitution, at independence in 1963 made provisions for the existence of two Houses, the lower (House of Representatives) and the Upper House (Senate).

The Senate was, however, abolished in 1966 with the amendment of Act 19 of the Constitution.

At independence the country was divided into 41 districts which made up the Senate. Abolition was aimed to cripple devolution.