Misinformation could hurt response to coronavirus

Kevin Mabonga

“We’re not just fighting an epidemic; we’re fighting an infodemic.” Those are the words of Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, World Health Organization (WHO) director general at a meeting of foreign policy and security experts in Germany on February 15.

He was referring to how fake news has become a major problem in dealing with the Covid-19.

From the day coronavirus was declared a global pandemic, the spread of misinformation has been high, making it one of the biggest challenges in the fight against the virus.

Messages have been shared across media platforms on whether the virus is real, the symptoms and treatment.

With a good number of people consuming information through the internet, the threat of fake news has never been this great given the magnitude of the pandemic.

There have been trending hashtags behind misinformation for example #coronahoax, #Covidhoax spreading conspiracy theories about the pandemic.

Misleading messages have also been shared on social media platforms leaving consumers confused.

Some allege that some age groups are more susceptible to the virus, and that drinking alcohol kills the virus while others dismiss the impact of keeping social distance and wearing of masks as preventive measures.

Journalists have also been caught up in this crisis. We have seen cases where misleading information is shared through the mainstream media or individual journalists.

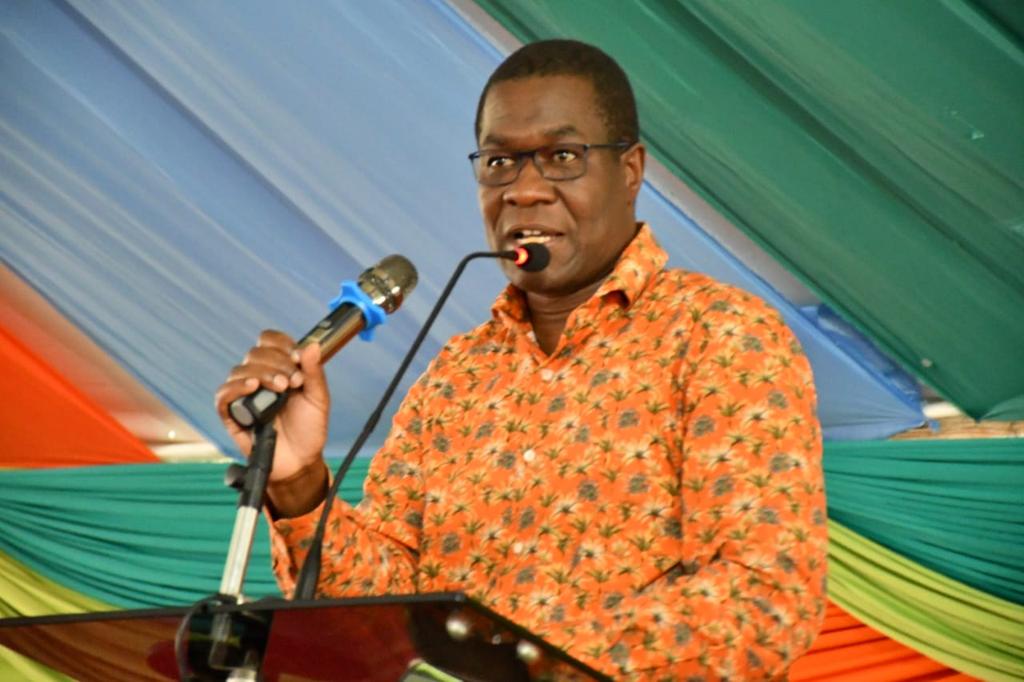

Mr Victor Bwire, head of Media Development and Strategy at the Media Council of Kenya, has cautioned journalists against publishing information that could be misleading.

He notes that with too much information about Covid-19 in circulation, journalists should publish information whose source is credible.

The Code of Conduct for the practice of journalism in Kenya calls on journalists to write a fair, accurate and an unbiased story on matters of public interest.

Several organisations have come out to fight misinformation about the virus.

Twitter updated its guidance on combating medical misinformation that goes against international public health guidance while Facebook committed to removing information that could cause physical harm.

Facebook deleted a video from Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro that claimed hydroxychloroquine was effective in treating the virus.

Previously, Twitter deleted a tweet by Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro on homemade treatment.

WHO has also been in the forefront in fighting misinformation by ensuring accurate information reaches as many people as possible.

Notably, WHO’s partnership with Rakuten Viber gives it the potential to reach over a billion people in their local language directly through their mobile phones.

On April 19, UN secretary general António Guterres joined the campaign against misinformation calling on solidarity.

Through tweeter he noted “Around the world, people are scared and are looking for sound advice.

This is a time for facts, science and solidarity, but a global “misinfo-demic” is spreading. Join us in rejecting the lies and hatred…”

Governments around the world are also trying to provide useful information about the virus to their citizens. This includes sharing updates on the status of the virus and guidelines to guide citizens to combat the disease.

Despite companies, organisations and governments putting up measures to fight misinformation, you have an important role to play as an individual.

Before you share any information consider the source and find out if it is genuine. Also check your biases, but most importantly, refer to credible websites like WHO’s. —The writer is a communications specialist