Kenya’s role in search of safe, effective HIV Vaccine

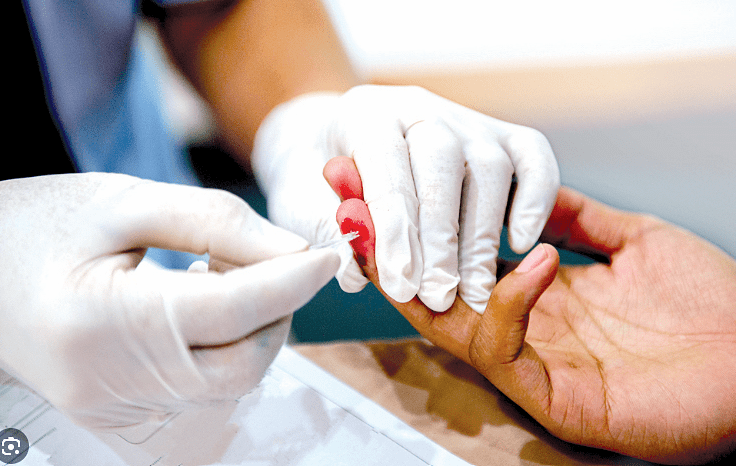

With data released every year indicating number of deaths from and new infections of HIV/Aids, scientists and researchers have been looking for new safe ways, through vaccines, of reducing transmission.

However, despite more than 25 years of research, there is no effective vaccine developed against HIV.

According to World Health Organisation (WHO), 48 HIV/Aids vaccine trials have been developed, with only one candidate RV144 HIV or the Thai trial making it to the third phase.

It is the first and only trial to-date to demonstrate modest positive outcomes in 31 per cent of the more than 16,000 adults enrolled in the clinical trial. However, it was not high enough to be considered substantively impactful on HIV prevention.

The HIV Vaccine Trials Network (HVTN)has four clinical trials assessing the effectiveness and safety of vaccines.

These trials are underway in parts of Africa (HVTN 702 or Uhambo, 703 or Antibody Mediated Prevention and 705 or Imbokodo), and in North America, South America and Europe (HVTN 704).

Locally, Kenya Medical Research Institute (Kemri), Kenya AIDS Vaccine Initiative- Institute of Clinical Research (KAVI-ICR) and several other research hospitals are part of this global effort to fight infections.

In 2017, Kisumu county participated in the HVTN 703, where 61 women were to be studied for two years under Kemri and Centres for Disease Control and Prevention collaboration. Results will be out by 2022.

In September this year, KAVI-ICR enrolled the first volunteer in the IAVI-W001 study to assess the safety of a HIV vaccine candidate called BG505 SOSIP.664 gp140 and to determine if it induces the human immune system to produce proteins known as neutralising antibodies. This marks the 12th HIV vaccine trial conducted by the research body since 2001.

Besides vaccines, the country was also the first to give a nod to the use of Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), a set of HIV drugs taken by HIV-negative people to prevent infection.

Benson Edagwa, assistant professor of pharmacology and experimental neuroscience, says vaccines were made in the laboratory from proteins that resemble HIV virus fragments.

“These laboratory proteins do not cause infection, but are intended to teach the body how to recognise and fight against HIV invasion by either stimulating cell mediated immunity or antibody (proteins released by our bodies to fight infections) production.

There have been multiple attempts to produce an effective HIV vaccine, but unfortunately, none of these efforts have been successful,” he explains.

There are many hurdles against the HIV vaccine. For instance, they have had to overcome lack of a good animal model or natural human cure, or even the genetic diversity of HIV, which is greater than any other pathogen.

“Some challenges organisations and investigators engaged in HIV vaccine trials face include limited funding needed to sustain long study durations that could last for several years, limited resources to produce and translate educational materials for participants and local communities, challenges in recruitment and retention of participants, especially after repeated vaccine clinical trial failures,” notes Edagwa.

While ongoing efforts to identify and develop effective vaccine strategies could change the landscape of HIV management, a significant hurdle to be overcome is how to deal with the rapidly mutating virus resulting in development of resistant strains.

With the rapid pace of science and multiple approaches being pursued, one could predict that interventions that integrate user preferences will soon be realised.