Haemophilia, the expensive disorder that halts children’s play

Injuries that result in bleeding happen. Nosebleeds, too happen. Children, especially boys go out to play and return with one injury or another; parents expect them.

But for Moses Muthii, bleeding after a small bruise while playing with his friends was anything but normal. Whenever he hurt himself, he would bleed a lot and his parents would have a difficult time getting the bleeding to stop. “My friends would refuse to play with me, because they feared they could hurt me,” he recounts.

He also recalls missing school for at least two weeks every time he got hit playing. His gums would bleed for almost a week when he removed his baby teeth to allow the adult teeth to grow.

Moses eventually learnt that he was a hemophiliac when he was 15 years old. “When I turned 15, I went to hospital to get circumcised. I bled so much that I had to be transferred to Kenyatta National Hospital where they diagnosed me with hemophilia. I would undergo training, which has enabled me to live a normal life despite my condition being mild,” narrates the ornamental bird farmer from Kagio, Kirinyaga County.

Sydney Baraka’s story is similar to that of Moses, only Sydney’s case is severe. His parents knew he was a haemophiliac when he was two weeks old. “Growing up, I remember my mother’s ardent warnings not to play rough games. She explained about the condition to me and asked me to play in the backyard,” he remembers.

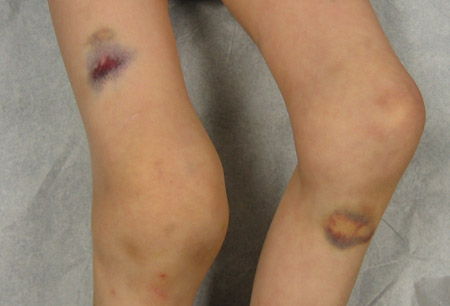

He, however, would sneak out and go to play football with his in the estate and would often come back with swollen or bleeding joints. He would miss school for days as he sought medical care. He would also get nosebleeds whenever it was hot. His parents also spoke to school administrators who banned corporal punishment for him.

“It was hard making friends in primary school as my schoolmates would wonder why I was not beaten by teachers as they were. It was also mentally draining as being out of school for long affected my academic performance, which in turn affected my self-esteem.

“Over time, I learnt how to be more careful. In high school, for instance, I missed very few school days as I could take better care of myself. I would play a lot of indoor games, go for walks, and swim,” Sydney candidly shares, adding that he is in campus now and living a normal life in the company of great friends who understand him.

Hemophilia is a hereditary and sometimes acquired blood disorder, where a person lacks blood proteins, known as factors that help with blood clots.

In the absence of the factors, blood does not clot which means that a simple cut can result in prolonged bleeding that can last hours or weeks. There are three types of haemophilia, haemophilia A where patients lack factor 8, haemophilia B, where patients lack factor 9 and haemophilia C where patients lack factor 11.

In Kenya, patients suffer from haemophilia A and B alone. Prevalence of the bleeding disorder is uniform in all populations regardless of race or geographical location. In Kenya, one in every 10,000 people is hemophiliac.

The Kenya Haemophilia Association has around 1,000 people on their register, which is about 20 per cent of all hemophiliacs in the country. The unregistered number of people can be attributed to people living in rural areas, far away from care and health facilities who might not know that they have haemophilia.

Genetically inherited

Dr Kibet Peter Shikuku, a haematologist and lecturer at the University of Nairobi, School of Medicine says haemophilia is a largely male disease with females being carriers. “Platelets, which help with blood clotting are produced by the X-chromosome.

When you get an abnormal X-chromosome you are not able to produce platelets necessary for clotting. Men only have one X-chromosome, which means that if they get an abnormal X-chromosome, the symptoms of haemophilia will manifest. Women have two X-chromosomes, which means that they will be carriers, but the symptoms will not manifest,” Dr Kibet explains.

He explains that while the disease is hereditary, it can be acquired when a person has a bacterial infection and the body produces antibodies that destroy their platelets and factors, when someone gets a cancer that destroy the factors, or during some surgical interventions where resulting infections destroy factors responsible for blood clotting.

The disease manifests different symptoms depending on whether the patient is a severe, moderate or mild bleeder. “Severe bleeders have less than one per cent of the normal level of factors in circulation and can bleed without trauma, for instance, even when sleeping.

Moderate bleeders have between two and five per cent of factors in circulation, while mild bleeders have six to 45 per cent of factors in circulation and tend to lead normal lives unless subjected to trauma,” he offers.

What to look out for

Dr Kibet shares that haemophiliacs can be diagnosed from birth. Haemophiliac children born normally tend to have a tower head (bigger than normal head).

They also bleed longer than normal when the umbilical cord is cut and when they get vaccinated. When they start crawling, they swell on the places of impact. Their gums also bleed a lot when teething begins.

For bigger children, they normally get a sensation called an aura, before they bleed. “They can normally tell when they are about to start bleeding. Bleeding normally happens around the joints, such as ankles and knees.

The bleeding can, however, occur in other areas, such as the gastro-intestinal tract and even in the brain, which can be life threatening. If the bleeding is not treated, young children can form deformities and become lame. In some cases, death can occur,” he explains.

Treatment and care

Dr Kibet reiterates the importance of proper care, treatment and management after diagnosis. There are various treatment options available.

“We often give blood plasma from a normal person to the hemophiliac patient, which helps them form clots. This is done if there are no factor concentrates. Patients can stock factor concentrates, which they can inject themselves with whenever they get an aura.

“A hemophilia A patient, for instance, injects themselves with the factor 8 concentrate. If the patient has antibodies against the factor concentrates, we also give them a bypass agent to fight the antibodies. Hemlibra, a more superior drug that stops bleeding for longer is also at times available,” Dr Kibet adds.

Moses, however, notes that the drugs are expensive and not readily available. A dose goes for at least Sh150,000. Hemophiliac patients, therefore, have to rely on donor aid, with most of their treatments being donor-funded. Haemophilia patients nationwide would appreciate government aid to help secure haemophilia treatment so that it is more affordable and accessible.

He believes that community drives, such as the ones organised by Kenya Haemophilia Association, where communities and schools are sensitised on haemophilia are an important part of ensuring that haemophilia patients have support from the society.

With medication, Sydney and Moses share that they are able to lead normal lives. They emphasise the importance of having a support group of friends and family who understand and are supportive. To anyone newly diagnosed with haemophilia, Sydney’s message to them is hope.

“Do not be discouraged. You are just a haemophiliac. You are not disabled. You can lead a normal life as there are various treatments to help you with that. With a few lifestyle changes, such as consistently eating an iron-rich balanced diet and engaging in mild exercises, you can live a productive life,” he offers.

Dr Kibet recommends no high contact games and no long-distance walks for hemophiliac patients. He advocates for the patients to manage their weight as the joints may get inflamed and bleed when they gain weight.

Any hemophiliac patient or career should also have a hematologist present during surgical interventions. Hemophiliacs should, for instance, go to a hospital for circumcision, and Kenyatta National Hospital, for example offers safe circumcision for them.

Mothers who are carriers should have a haemotologist present during delivery in order to guard against excessive bleeding, which can lead to death.