Flowers bloom for the small farmer

Small scale farmers across the country are making a fortune from cut flowers, a segment of horticulture previously considered a preserve of large scale growers.

Many have embraced summer flower farming, which unlike greenhouse farming, does not require high capital to start as plants are grown in open fields.

Summer flowers, annual and perennial blooms traditionally grown during summer season in Northern Europe, are mostly used to blend other flowers to make a perfect bouquet.

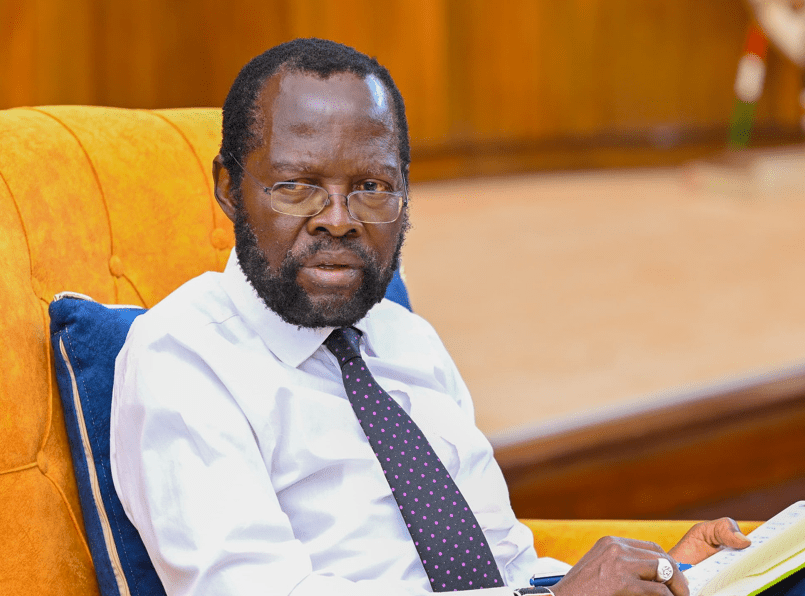

Edward Wanjohi, a Rumuruti farmer, has grown summer flowers since 2016 under the umbrella of Exceeding Grace 2016, a group he chairs.

The group, comprising 60 members, has 70 acres of land under flowers in Thome, Rumuruti, Laikipia county.

They practise contract farming which requires farmers to sign an agreement to grow crops for a specific buyer at a pre-determined price. The group is contracted to a Thika-based flower exporting firm.

On the farm, Wanjohi and his colleagues grow Mobydick flower, a milky bloom akin to Datura stramonium considered a weed in many communities.

He also grows other summer flowers such as Arabicum and Tuberosa on rotation as dictated by clients needs. Unlike conventional flowers, Mobydick is harvested for its fruit, not petals, and sold as fruits on a stalk.

Wanjohi says good quality flowers have a thin stalk, about eight inches long, with five or four fruits on it. One stick with five buds retails for Sh5, with a single plant producing several such twigs.

An acre of land holds approximately 2,500 plants translating to about Sh1.3 million an acre, according to Wanjohi. “Mobydick is a hardy plant that takes about four months to mature after which you can harvest it for five consecutive years,” he says.

Before they ventured into growing summer flowers, Wanjohi and his colleagues grew green grams and maize, but abandoned the crops because of low returns on investment.

Strict contractual agreements

But it has not been rosy. The farmers have had to deal with several challenges, including insecurity, poor roads and water scarcity.

To overcome the challenge, Wanjohi and his counterparts invested in a dam and tapped water from a nearby river and hired private security in addition to the Kenya Police Reservists who man the area.

“The surrounding community is mostly pastoralist hence aren’t much into flower growing. Sometimes animals, both domestic and wild, trample the flowers. Luckily, elephants and cows do not eat this plant,” said Wanjohi.

He also respects his contractualobligations with the flower buyer. “We must stick to the calendar given by the contracting firm, hence, we plant and harvest in intervals. If we don’t stick to the contract our flowers will go to waste,” he says.

For economically viable Mobydick farming, a flower commonly farmed in Laikipia and Baringo, Wanjohi suggests that one does at least one acre.

Wanjohi’s group has an arrangement where members earn Sh150,000 from an acre of land after three months.

However, a member can only farm the crop other members of the group are planting to enable the team to benefit from economies of scale, a model he says, was inspired by Israeli’s Kibbutz system.

“Last year, the country experienced a shortage of two million Mobydick stalks. There is a ready market for these flowers locally and abroad,” he says.

Acquiring seeds is the most expensive aspect of farming Mobydick with a kilo of seeds, enough to plant an acre of land, going for Sh25,000. Luckily, the crop can last for five years after planting.

Wanjohi advises young people seeking employment to go into agribusiness.

“Youths should go into agribusiness. Once they do that they’ll no longer need to depend on handouts from leaders,” he adds.

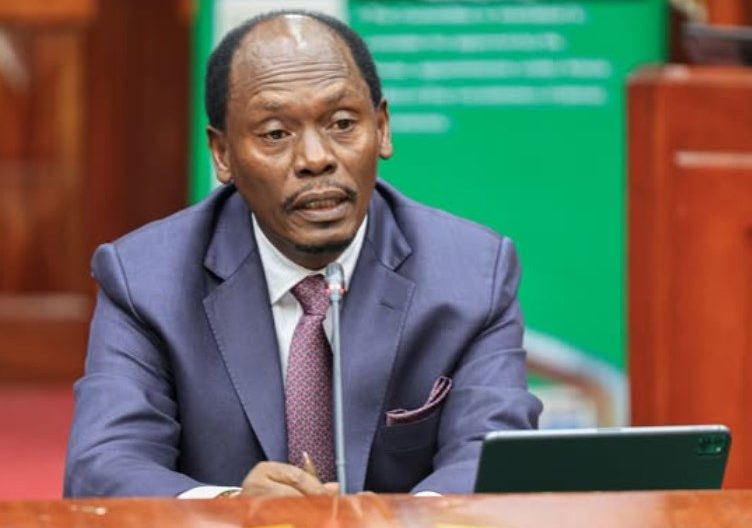

John Maina from Kamburu in Lari, Kiambu, has also discovered the hidden treasure in summer flowers. He grows Arabicum flowers, a bulbous plant resembling an onion bulb, sold for its stalk and petals.

With a quarter an acre producing 25,000 stems, he sells a stem at an average of Sh4 translating to approximately Sh100,000 per quarter acre.

The price, from his various buyers based in Thika and Limuru, however, varies depending on the season, and can be as high as Sh17 or as low as Sh0.5 per stalk.

Unlike Wanjohi who engages in contracted farming, Maina is freelancer, who sells to the highest bidder.

The buyers grade the stalks in six categories depending on length starting from 60 centimetres to 85 centimetres. Rarely do dealers buy stalks less than 60 centimetres tall.

High season begins from around Valentine’s celebrations to June, the rest being low season.

“We sell the flowers throughout the year except February and March when the market in Netherlands is flooded. A good quality flower consists a cone head with only a few open petals,” he says.

Acquiring the seeds is expensive, with a bag of 800 bulbs going for Sh3,000.

A quarter an acre uses 25 bags, as the bulbs are planted closely together with the big bulbs requiring a spacing of 10 square centimetres, the medium ones eight square centimetres, while the smaller ones require only four square centimetres.

Luckily, the bulbs too reproduce at a rate of one and a half bags or two bags for every bag of bulbs planted, and are sold as seeds to willing buyers. He also sells the bulbs, planted as seedlings, at Sh3,000 per bag.

After planting, the flower takes between two and a half and three months to mature after which it is harvested over a period of six weeks.

The bulbs must be stored for at least two months before planting to season them.

Maina began farming summer flowers in 2005 experimenting with Mobydick, Eligium Planum and Ammi Visnaga flowers before settling on Arabicum. From three buckets of flower bulbs costing Sh350 back then, Maina now plants about 80 bags of Arabicum seed per season.

Organic manure is the most expensive input at Sh30,000 per lorry load while the most arduous task is harvesting the flower bulbs.

Economically viable

Other challenges include price inconsistency due to brokers, blight, stalk borers, and erratic weather.

To deal with the challenges of failed rains, Maina has tapped water from a nearby stream, which he uses to irrigate his farm.

His sentiments are shared by Muigai Ndiba, a Limuru farmer, who has been in floriculture since 1996.

“You have to know your planting calendar so that you harvest during the high season when the prices are good.

“Additionally, you must prepare your land well and take good care of your crops,” says Ndiba.

Just like Maina, he also grows Arabicum flowers on a half acre plot in Limuru. He considers bulb rot, a disease that affects flower bulbs, his biggest challenge so far.

To cut on costs, Maina propagates his own seed and has built a bulb storage shed worth Sh20,000.

For economically viable Arabicum flower farming, Maina advises that one start with at least a quarter an acre.

“With Sh50,000 you can easily earn another Sh50,000 in profit. Even if you have a larger area, say an acre, don’t put all of it under the crop since you have to rotate the flowers once a year,” he says.

From the venture, Maina has built a four-bedroom semi permanent house, took his daughter through a self-sponsored degree programme and bought two dairy cows to supplement his manure needs.

“There is life in flower farming. It has minimal expenses, pretty much like farming sukuma wiki,” he says.

Ndiba, on the other hand, has managed to acquire several parcels of land from the proceeds of flower farming including four acres in Limuru and another two acres in Kinangop.

Existence of flower dealers, such as Thika-based Wilmar Flowers, has enabled the smallholder farmers participate in international floriculture business despite lacking the means to export their produce.