Activists turn to local campaigns to beat FGM

Manuel Ntoyai @Manuel_Ntoyai

Grassroots level organisations, rescue centres and other key stakeholders have been forced to change tactics and turn to short term propositions, each tailored for local communities around them.

Grace Sekento from Marie Adelaide Girls Rescue Centre in Kajiado county, which rescues Maasai girls from forced marriages and Female Genital Mutilation (FGM), says lockdown due to Covid-19 revealed new information that required new strategies.

“When we investigated some cases we handled during lockdown, the common denominator was poverty and ignorance, where some parents took advantage of the situation to conduct FGM it secretly,” she says.

With the rescue centres closed, activists could not let their guard down. They rescued 15 girls who were either about to be married off, or to undergo the cut.

“As a centre, we had an outreach programme with local churches and schools. Through them, we are able to reach out to girls and get information quickly, but when the two closed, it was hard to do sensitisation campaigns with the aid of local administration alone,” she adds.

As the fight continues, Grace says it is important to recognise rescue shelters as essential services whose closure has major effects on girls and young people. She calls for strengthening community systems for child protection by hiring and training more children protection officers, security officers, judicial officers and strengthening referral mechanisms.

Alternative rites

The Maasai community has seen a reduction in FGM cases, with campaigns such as the annual Alternative Rites of Passages (ARP). The ARP is a community-driven initiative supported by Amref Health Africa and other organisations that retains cultural celebration of a girl’s transition into womanhood without the cut, or early/forced marriage.

Keekonyokie North area chief, John Ole Sayo, says years of working together with stakeholders has helped in the fight against the menace.

“Two years ago, we had a successful ARP ceremony where more than 300 girls graduated. One of the key things we wanted to find out was whether parents had a change of mindset after years of campaigning and making them understand effects of FGM not only to the girls, but to the community,” he says.

Statistics from the 2014 Kenya Demographic Health Survey showed the overall prevalence of FGM in Kenya has decreased from 38 per cent in 1998 to 32 per cent in 2003 and to 27 per cent in 2008 among women between the ages of 15 and 19.

During lockdown, with the girls at home, cases of teenage pregnancies also spiked and his area was not spared. Those rescued from early marriages were taken to centres, where they were quarantined before being integrated with other girls.

“With the help of our partners we were able to put some structure to help us in this fight at village level. Once schools reopened, I had assistant chiefs and village elders go to every part of the location to look for girls and even boys who had dropped out,” he adds.

His words are echoed by Robert Aseda, the programmes director at the Network for Adolescent and Youth for Africa, an organisation that focuses on sexual and reproductive health and rights advocacy.

“These teams were one of our sustainability strategies to complete our work when we are not working directly with members of the community. With minimal field activity engagements due to Covid-19 and transition of programmes, we have built more capacities in these teams from rescue to follow up strategies on the legal fronts,” says Robert.

Roberts says the team comprises other technical figures such as the head teachers and curriculum support officers who helps monitor FGM situation, drop outs and transition in schools, which is key in establishing progress.

“We still need to hold dialogues with community on the impact of FGM and other harmful practices while disseminating key policies and laws on including the FGM Prohibition Act 2011 and county-specific FGM policies to enable the public understand the law, the legal repercussions and their role in ending FGM,” he says.

Kajiado county was among the first to put into place such policies, by domesticating the national FGM Prohibition Act 2011.

“The County government of Kajiado developed the policy to ensure ownership by the county and the community and to enable it allocate budget and other resources including personnel to eradication of FGM. International partners and UN agencies such as UNFPA provided technical support in the domestication process and launch,” states Robert.

Men’s involvement

Tana River-based activist Sadia Hussein says during lockdown, girls were locked in their homes, making it difficult to reach out to them.

“Schools act like safe houses. When girls were at home, some remote areas and with minimal transport, it became harder to get to them when we got reports they were being cut,” she says.

Sadia says she had to readopt to Covid-19 situation. While issuing and distributing masks, she was able to reach out to some parents.

“At the end of the day, we took to social media to get the focus on issue because everyone’s mind was on the pandemic, while the cuts continued. We run the Hashtag #ENDFGMPREVENTCORONA, which reached five million people globally,” she says.

Use of local media has also helped activists to reach out to communities in remote areas to continue with the sensitisation campaigns.

Sustained efforts by the Anti-FGM board have not gone unnoticed with more men turning up in large numbers for anti FGM sensitisation meetings and denouncing the act.

Men led campaigns such as Men End FGM continues with meaningful engagement across the country, especially in pastoralist communities.

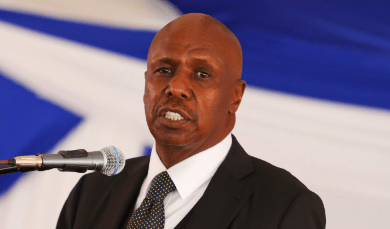

With one of its directors, retired Kadhi Rashid Omar leading the offensive in North Eastern region through engaging Islamic and cultural leaders advocating for the end of FGM practice in the region.

“Arabs in Kenya and across the world do not cut their girls/women yet most are Muslims. Why then are Muslims cutting their girls in Kenya? FGM is not part of Islam and must be condemned,” said Omar.

“FGM is a burden bestowed on women and girls by us in the name of culture. We need to rise and say enough is enough since FGM is everyone’s responsibility and a violation of human rights,” says the boards CEO Benardatte Loloju.