Overcoming the horror of maternal sepsis and living to tell the tale

Harriet James @harriet86jim

In May 2017 on a Monday night, Regina Wabuko successfully delivered twin girls and having no complications, she was discharged the following day.

However, things went awry a day after she reached home.Her body felt uneasy and since she had been told that the body goes through some changes after birth, she ignored the pain.

“I was always exhausted, in pain and just generally felt unwell. I felt dizzy and could not eat or even drink water, yet I needed to breastfeed my babies.

But almost a week of staying at home, I started feeling chilly constantly and I knew that something serious was going on and that I had to go see a doctor,” Regina narrates.

At the hospital, several tests were conducted and it was discovered that she had developed maternal sepsis, coupled with malaria.

“During the delivery of my daughters, I had prolonged labour of about 48 hours and then I had an episiotomy, because my first baby was too big.

The doctors concluded that is how I got infected,” she continues.

Major cause of death

The World Health Organisation (WHO) defines sepsis as a life-threatening condition that is brought about when the body’s response to infection results in injury to its own organs and tissues.

If sepsis develops during pregnancy, while or after giving birth, or after a miscarriage, it is called maternal sepsis.

Since infections in most instances complicate serious diseases, the condition is a final common pathway to death in both communicable and non-communicable ailments globally.

In a case-cohort study among post partum women admitted at Pumwani Maternity Hospital published in the Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology of Eastern and Central Africa, of the 676 patients contacted at seven days postnatal, 59 patients met the criteria for diagnosis of puerperal sepsis based on reported clinical symptoms.

This corresponded to a prevalence of 8.7 per cent, for sepsis. Based on the 14 days postnatal interview and clinical examination, 69 of 566 women met the criteria for puerperal sepsis diagnosis based on reported symptoms and clinical examination; corresponding to a prevalence of 12.2 per cent, for puerperal sepsis.

Puerperal sepsis is the infection of the genital tract occurring at labour or within 42 days of the postpartum period.

The 2015 report titled Prevalence and risk factors for puerperal sepsis at the Pumwani Maternity Hospital associated occurrence of puerperal sepsis with obstructed labour, multiple vaginal examinations, and Caesarean section.

Globally, according to WHO, maternal mortality still is “unacceptably high” as the statistics indicate that nearly 830 women die from pregnancy or childbirth-related complications every day.

The vast majority of these deaths occur in low-income settings, and it is estimated that 98 per cent could be prevented.

Despite it being the third leading cause of maternal death, maternal sepsis has received less attention when it comes to research, especially in the country.

Despite the fact that the condition can be prevented, maternal sepsis still continues to be one of the major causes of deaths and morbidity for recently expectant mothers.

It can be as a result of bacteria, which can enter the body through inhalation, contaminated surgical instruments, a poorly disinfected theatre, drinking contaminated water and general poor hygiene.

“Its causes, include mastitis, septic abortion, infected wounds, malaria, meningitis, respiratory tract infections and urinary tract infections.

Common signs and symptoms, include abnormal vital signs, headache, dizziness, fever, chills, abscesses, joint pains, foul-smelling vaginal discharge, tender uterus, pelvic pain and prolonged bleeding,” explains Dr David Thuo, a consultant obstetrician-gynaecologist and fertility specialist.

He says late-onset neonatal sepsis begins after 24 hours of delivery and can come as a result of viral, bacterial or fungal infection.

There is a higher risk of late-onset sepsis if the infant spends time in the hospital to receive treatment for another health problem or comes into contact with someone who has an infection.

“It is possible to treat sepsis at home with antibiotics should there be early detection and if the condition hasn’t affected vital organs.

However, those with severe sepsis and septic shock need admission as sepsis can kill in 12 hours after infection. The blood infection is what kills faster,” he explains.

Regina was told by her doctors that her white cells count had doubled and that if she had not been to the hospital that day, she would have lost her life. She was admitted immediately and antibiotics given via drip for a whole week.

“I am fully recovered. My episiotomy wound healed, my body recovered. I don’t know if it will be back honestly, I was never told it will be back because I think the antibiotics did the work,” says a hopeful Regina.

When she checked out, she was prescribed more antibiotics and was advised on how to take care of herself to heal from the baby birth wounds and prevent further infections,such as sitting on salty water.

Regina views her healing as a second chance at life and from time to time shares her experience on social media to educate women on the condition.

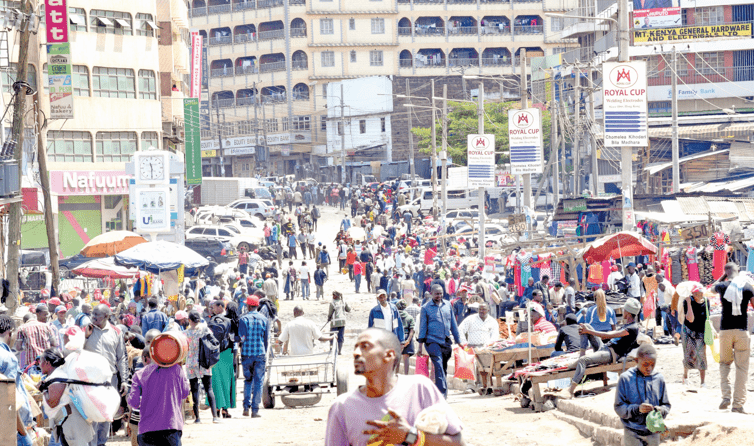

Overcrowded health facilities

Dr Thuo adds that other factors that might cause the condition, include women using health facilities that are overcrowded as well as being poorly resourced places them at greater risk.

He says in most instances, health care workers are often unaware of the signs and symptoms of sepsis and so are unable to recognise the condition and treat it in time.

o prevent it, women need to be up-to-date with their routine vaccinations, minimise the number of vaginal examinations during labour, ensure that whoever touches their private parts during birth washes their hands.

“Women should also contact their health care provider should their membranes rupture prematurely, or suspect an infection and follow instructions regarding their vaginal area or their surgical incision,” he offers.

Dr Thuo recommends that women go to the antenatal clinic for screening and training on how to prevent maternal sepsis.