Human Rights: Relief for families raising intersex children

By Betty Muindi, August 21, 2019In two months, the Kenya Certificate of Primary Education (KCPE) examinations will kick off. As other pupils get ready, Jane Njeri* is uncertain she will sit her exams.

Njeri is on the verge of being locked out of the examinations because she was born with both male and female genitalia. Her school fears that invigilators amid tight exam rules may deny her the chance to sit for the examinations.

“The school has asked me to present a doctor’s medical summary showing my daughter’s disorder, but requests to Kenyatta National Hospital have been unyielding,” says a desperate Mary Wangui*, Njeri’s mother.

Sitting in one corner of the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights (KNCHR) boardroom, Njeri is stressed.

The human rights body is the only hope she has to achieve her dream of becoming a doctor one day. “I have been stigmatised by everyone for as long as I can remember. I pray the government does not also let me down,” she says.

It all started when Wangui gave birth to her child in 2004 at home in Eldoret. “I was shocked when I saw my baby with two sexual organs.

Clinicians at a local dispensary advised me to seek further assistance from Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital (MTRH) in Eldoret where doctors just looked at my child and decided to assign it the female gender,” she recounts.

Wrong surgery

They advised her to raise the baby as a girl for one year after which they would perform corrective surgery to remove the penis. After one year, the penis was cut off.

However, as Njeri approached puberty, her physical characteristics and behaviour became more male than female. Her muscles and chest started growing and her voice became deep.

“My daughter has never been happy doing girly things. She has always protested wearing dresses and likes to play games with boys,” she explains.

Concerned about the new developments, she took her for more tests at Kenyatta National Hospital. Further extensive tests and examinations at Lancet Laboratories confirmed her child was actually a boy.

Njeri was found to have XY chromosomes, and so was considered male. There were higher levels of testosterone, she had no vulva, no uterus or any other characteristics of a female.

“I panicked. I knew the doctors at MTRH had messed up my child’s life. The hospital recommended more surgeries and prescribed hormone tablets to boost breast development and enhance her female secondary sex characteristics.

But still, at 15, her breasts are yet to grow,” she says amidst tears. Had she known better, she wouldn’t have taken her child for surgery.

KNCHR is consulting with the Kenya National Examinations Council so that Njeri can be cleared to sit for the upcoming national examinations, which would start on October 28.

Njeri is not alone; Peter and Irine Maingi are parents to an eight-year-old who is an intersex. Their child was born with smaller than usual genitalia and when a routine physical check was done, they found the testis had no testicles.

The baby had no female genitals. “We were confused. We had never encountered something like that. I started researching further about this new phenomenon,” says Maingi.

The father of three says a scan later revealed that their child has one ovary that had a testicle attached to it also known as ovotestes on the left and a hanging fallopian tube. There was no uterus.

All these meant that the baby, whose phenotypical attributes showed him as a boy was actually a girl. The blood tests showed that his chromosomes were XX46 confirming she was a girl.

Taskforce recommendations

“I have used over Sh4 million in reconstructive surgeries and tests, which have seen me declared bankrupt and my property auctioned,” says Maingi, a businessman.

They are set to travel to Boston Children’s Hospital, in the US for comprehensive corrective surgery on the now eight-and-a- half-year-old child, but they lack finances.

“We were asked to go for the surgery before our child turns eight because the ovotestes could become cancerous if not corrected early, but we haven’t been able to raise enough money,” says Maingi, who is now appealing to well-wishers to help him.

This is a roller coaster that thousands of other parents of intersex children find themselves stuck on.

Estimates by the United Nations for Human Rights show that in every population there are around 0.05 per cent to 1.7 per cent babies born as intersex.

This means that using the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) population estimates of 47.8 million people, the intersex population would estimate about 23,925 to 813,425. These people, however, live in the shadows because of societal stigma and shame.

“We haven’t told anyone including close family members and friends that my child is intersex. I cannot bear to see my baby being ridiculed. If they ridicule her because of her tomboy nature, how much more will they do it if they get to know the truth?” poses Mary whose husband left her because of their child’s condition.

On the other hand, Maingi has had to transfer his child to three different schools because of unwanted attention that has become part of their child’s life. One of the sources of ridicule for his child is that despite having a functioning penis, he urinates like a girl.

In 2009, a woman went to court after doctors wrote a question mark on her child’s birth papers instead of a gender. She wanted identity documents for her child to be able to attend school, a law preventing surgery on intersex children unless it is medically necessary, and proper information and psychological support for parents.

As a result, in what became a landmark ruling, five years later, the High Court ordered the government to issue a birth certificate to the child.

The Attorney General was then ordered to create a task force that would look at ways of providing better support for intersex children.

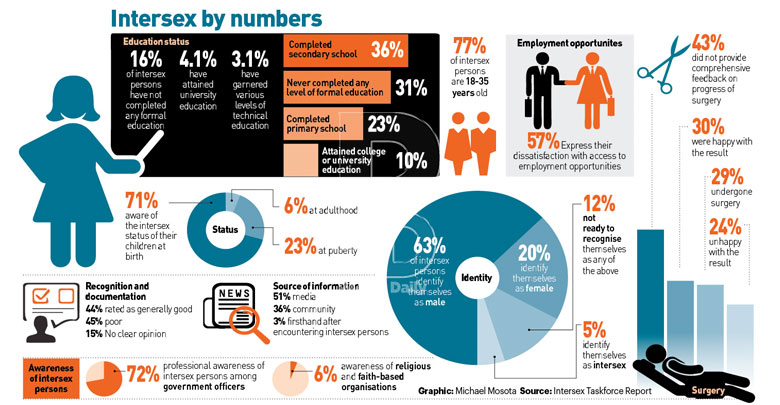

That task force dubbed Intersex Taskforce on policy, legal, institutional and administration reforms regarding the protection and treatment of intersex persons in the Republic of Kenya in April this year handed its recommendations to the Attorney General.

Following the recommendations and years of lobbying by intersex persons for the first time this Friday, in the country’s, the continent and the world’s history, intersex persons will be counted during the country’s national census.

Inclusive environment

During the census, families will be asked if they have an intersex family member and they will be given an I-marker, an intersex identifier, which will eventually be used in public documentation.

Jedidah Wakonyo, Commissioner of the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights, says intersex persons for a long time have not had an opportunity to be recognised.

“It is important to accept that there is a third gender, it is called Intersex, an in-between gender. These are people with ambiguous genitalia and it is imperative to include laws that protect them,” she explains.

This, she says, will also ensure ease of acquiring documentation such as identification cards by providing a box where intersex people can tick just like others who are either male or female.

Also, other changes following proper data of the actual number of intersex persons will facilitate designing special restrooms in schools and public spaces as well as introduction of gender non-conforming school uniforms so that intersex children are comfortable in school.

“The only concern we have at the moment is whether people will come out and identify themselves as intersex due to the stigma involved, making it difficult to establish their exact population,” she fears.

On this, the chairperson of the Taskforce on Intersex Persons, Mbage Ng’ang’a assured Kenyans that enumerators are trained and have taken a secrecy oath and, therefore, this information will be treated with utmost confidence.

“We encourage intersex persons and parents of intersex children to take full advantage of this opportunity to proudly come out, identify and be counted under code 3 as intersex in the Friday’s counting exercise,” he said.