Fishermen breathe life into Kenya’s dying coral reefs

By Reuben Mwambingu, October 8, 2019A Wasini Island-bound speedboat leaves Shimoni’s mainland jetty in the South Coast and glides across the turquoise waters of the Indian Ocean.

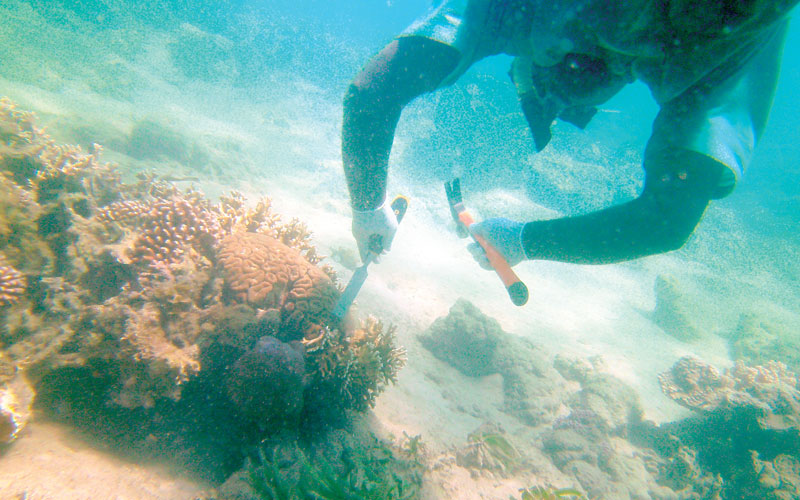

As the boat approaches the island, it slows before it comes to a halt, allowing a group of youths aboard to dive into the ocean.

Their mission? To restore the coral reefs suffering degradation or mass bleaching, as marine scientists call it.

Ahmed Mohamed Abubakar, chair of the Wasini-based coral transplant team under Wasini Beach Management Unit (BMU), says they have been on the mission for three years now.

“In the past, this sounded Greek to us because none of us had the foggiest idea about planting corals. It was a new thing that requires keenness and patience, but at first, we had to be sensitised about the whole process.

We were first trained by East African Wildlife Society through Kenya Marine and Fisheries Research Institute (Kemfri) in 2014 and since then we have been planting coral because we know its importance,” he says.

Lasting solution

The ocean serves as a lifeline for the community, which relies on fishing for food and as the main economic activity. However, over the years, fisherfolk have witnessed a steady decline of fish, a situation that prompted them to look for a lasting solution.

It is against the above backdrop that Abubakar says they came to familiarise themselves with the coral restoration project and went on to form the coral transplant team.

This is a unique project in the country and only the second one in Africa after a successful one in Mauritius.

Understanding corals may be a complex thing, considering that scientists categorise them as living organisms, which feed and undergo usual growth and development, even though before the eyes, they appear more like a rock.

So what is a coral? Known as coral polyps, these are tiny, soft-bodied organisms related to sea anemones and jellyfish. At their base is a hard, protective limestone skeleton called a calicle, which forms the structure of reefs.

Dr Jelvas Mwaura, a reef scientist at Kemfri, says for a coral polyp to exist, it has to harbour algae also known as zooxanthellae, plant cells within corals, which manufacture food through photosynthesis hence providing important nutrients to facilitate the growth of the coral.

“When a coral begins, it grows together with algae symbiotically in the sense that algae manufacture food to help coral polyp grow and the algae is hosted by the coral polyp, which grows by producing calcium carbonate,” he says.

As the scientist explains, reefs begin when a polyp attaches itself to a rock on the seafloor, then divides, or buds, into thousands of clones. The polyp calicles connect to one another, creating a colony that acts as a single organism.

As colonies grow over hundreds and thousands of years, they join with other colonies and become reefs. Some of the coral reefs on the planet today began growing more than 50 million years ago.

According to Mwaura, most marine life relies heavily on the coral reefs for shelter.

“Of all marine life shelters including seagrass, mangrove and coral reefs, researched shows that coral reefs harbour the most marine life dolphins, fish, turtles, sharks and other sea creatures.

Therefore, you can imagine the biodiversity hosted by the corals and its implications to the society,” says the reef scientist.

However, he says, following widespread effects of global warming since 1998, a rare phenomenon that is mass bleaching of corals started being witnessed in a vast section of the Indian Ocean covering parts of Kenyan Coast all the way to South Africa.

“Corals are stenothermic organisms, which mean they only survive within a narrow temperature range. Slight rise or decrease in temperatures will stress the coral and eventually cause its death.

Coral bleaching, which occurs when coral polyps expel algae that live inside their tissues, was experienced in the Indian Ocean in 1998, but before that, it used to happen in the Caribbean and the Pacific Ocean,” explains Mwaura.

Marine pollution

Scientists explain that reefs around the world are declining because of marine pollution, climate change, coral diseases, and other challenges such as sedimentation and destructive fishing, where fishermen break corals in search for bigger catch.

Degraded corals automatically translate to stress in marine life and subsequently dwindling of the fish population.

Mwaura says in some reef areas of Kenya, coral cover has declined by 50 to 80 per cent in just the last two decades, thereby threatening livelihoods of millions of coastal peoples who depend on marine life for survival.

It is against this backdrop that Kemfri and other organisations embarked on the first-ever active reef restoration project in Kenya and the entire western Indian Ocean region using ‘coral gardening’.

The institute has trained hundreds of fisherfolk along with the Kenyan coast coral restoration technique, which involves collecting small pieces of healthy coral, raising them in underwater nurseries and then transplanting them to degraded sites.

“Coral gardening is a long process: it is a delicate operation, but a very interesting piece of research,” says Abubakar.

The restoration team begins the process by first sensitising the community including the fishermen to understand the importance of the project and establish its objectives, before identifying the area where reefs are degraded.

“We then go out to observe the degraded area to gather data, which will be used for monitoring the recovery trend,” he adds.

The third step involves hands-on training for the community to participate in the reef restoration.

Here, the team is trained in techniques such as moulding a cement disc on which a coral is planted before being taken to a nursery bed. They also construct nursery beds, which are reinforced with meshed wires.

Success signs

After the cement disc dries, they are taken to the restoration site, followed by the transplanting of coral fragments from donor healthy reef coral or loose coral by attaching them onto the constructed nursery blocks using waterproof cement.

“Transplanted coral fragments are placed in a sunlight-rich environment and allowed to grow to a size large enough to be out planted. They stay for at least three weeks.

After they have reached a substantial size, they are tagged and taken to a carefully selected reef restoration site where they are attached directly to the reef using a two-part marine epoxy adhesive,” Abubakar says.

“And the rest will be monitoring and maintenance of transplanted corals to ensure that they are free from pollutants that can degrade them,” he adds.

The project, according to Abubakar, has shown signs of success with fisher folk recording impressive returns in sea fishing.

“In the early 1960s fish were in plenty, but towards late 1990s there was a drastic decline, which experts said was as a result of the bleaching of corals. Now the latest data of 2015/16 show an increase in fish production locally.

In the 90s the best we could get was between three to 6kg per day, but now we can get between 10 to 15kg daily, with each going for Sh300,” Abubakar explains.