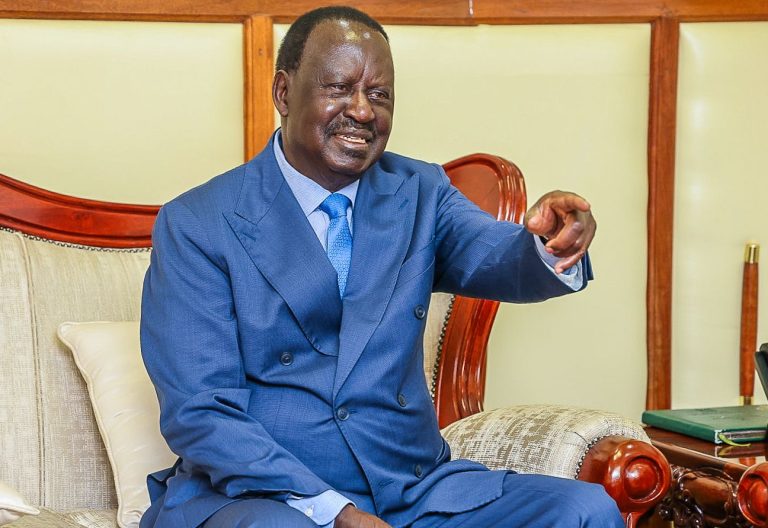

Raila: Liberation icon or power survivor?

Across the long sweep of Kenya’s history, few names stir as much passion, loyalty or controversy as Raila Odinga, aka Baba. To many, he is the father of Kenyan democracy, the indomitable lion of the opposition, and a champion of the people.

His long political journey from detention cells in the 1980s to ballot boxes in the 1990s through the 2000s, from protest streets in the 1990s to Cabinet rooms in the 2010s—reads like a national epic.

But history’s duty is not to flatter. It must probe, analyse and, when necessary, puncture myths.

When we strip away slogans and chants, when we cool the heat of political emotion, we face a central, unsettling question: has Raila been driven more by national purpose or by personal ambition?

To grasp the complexities of this question, we must situate it within the broader context of global political history.

Julius Caesar claimed to defend the Roman Republic even as he dismantled it (49 BC). Napoleon Bonaparte rode the revolutionary wave only to crown himself emperor (1804).

Winston Churchill, the great wartime leader, was no stranger to switching parties when his fortunes demanded it (from Conservative to Liberal and back between 1904 and 1924).

Otto von Bismarck engineered wars and reforms alike—not just for German unification but to fortify his own power (1860s–1870s).

Raila fits in this lineage of leaders whose pursuit of power is cloaked in the language of public good.

His role in the fight for multiparty democracy in the early 1990s, the symbolic ‘Kibaki Tosha’ endorsement in 2002 that ended KANU’s four-decade grip on power, and the push for the 2010 Constitution were undeniably critical and landmark contributions.

Yet, at every turn, Raila has shown a masterful ability to pivot, reposition, and survive—to find opportunities where others saw defeat.

In the late 1990s, Raila merged his National Development Party with KANU, the very regime he had long denounced, and took a cabinet post under President Daniel Arap Moi in 1999.

Was this a strategy to reform from within, or a self-serving compromise?

After falling out with Moi, Raila pivoted again, backing Mwai Kibaki in the 2002 election, delivering the opposition’s long-awaited victory that ended KANU’s rule.

When the Kibaki administration sidelined him, he mounted fierce opposition, culminating in the post-election violence of 2007–2008—which ended in a power-sharing deal installing him as Kenya’s second Prime Minister after Jomo Kenyatta.

Then came the famous 2018 handshake with President Uhuru Kenyatta, framed as national healing but widely seen as an elite pact insulating the political class and squeezing out rising opposition voices.

This came after he had boycotted the presidential re-election. Is that political genius or opportunism?

Sharp edge of principle

Today, Raila stands once more inside government—this time under the broad-based arrangement struck with the William Ruto administration after the 2024 Gen Z protests.

His lieutenants occupy key positions, calling shots and influencing policy.

How many secret deals have Raila negotiated within the governments he has been co-opted into since the Moi era?

I can only imagine he missed out on the Jomo Kenyatta presidency (1963–1978) by the accident of time.

Had Raila lived in colonial Kenya, would he have stood shoulder to shoulder with the fiery nationalists of the 1950s, or would he have manoeuvred among the elite collaborators like James Beauttah (1920s-1930s), Senior Chief Koinange (1940s-1960s), Waruhiu wa Kung’u (1940s- 1950s)—men who worked within colonial power structures, presenting themselves as intermediaries, sometimes out of survival, sometimes ambition, or often both.

These collaborators were not mere puppets; they were political survivors who understood the art of working the system. Does Raila not belong, by instinct, to their tradition?

By contrast, Kenya’s true nationalists—those who lived and breathed national liberation in the 1950s and 1960s—often paid with their careers, bodies, or lives.

Jaramogi Oginga Odinga, Raila’s own father, sacrificed comfort and access for principle, opposing Jomo Kenyatta’s centralisation of power in the 1960s and 1970s and further championing the democratic course in the 1990s.

Koigi wa Wamwere, tortured and exiled in the 1980s and 1990s, refused to bend. Gitobu Imanyara defied censorship and harassment through the 1990s and early 2000s.

Willy Mutunga, Chelagat Mutai, and Jean-Marie Seroney to name a few, stood on the sharp edge of principle, unwavering even when it cost them everything.

When critics call Raila a political survivor rather than a “martyr”, they point to this contrast. Where others fell, Raila adapted.

Where others paid the price, Raila collected the spoils. Is this wisdom or ambition?

To crown it all, the 2024 Gen Z protests illustrate this perfectly.

As young digitally savvy, politically awakened, economically battered Kenyans took to the streets to resist the punitive Finance Bill, facing the full weight of state repression: tear gas, bullets and arrests, Raila, like a vulture, watched from a distance, circling the unfolding crisis while calculating the right moment to swoop.

When the youth had spilt their sweat and blood, Raila stepped in—not as a protester, not as a resistor, but as a mediator, a broker, the indispensable elder statesman.

In doing so, he harvested more political premium than Gen Z.

This is not to erase his past sacrifices. Raila was known for detention in 1982 and exile in the 1980s, and police brutality.

He has, in many moments, challenged Kenya’s political establishment at real cost.

But as history teaches, sacrifice and ambition often live side by side. Napoleon bled for revolutionary France—even as he plotted his imperial ascent.

Raila’s defenders will argue that politics is the art of survival, that only the cunning endure. They are right—but that is precisely the point.

Raila’s brilliance has been his ability to navigate this treacherous terrain, but his tragedy may be that in doing so, he has too often chosen survival over transformation, positioning over principle, personal ambition over national renewal.

What then is Raila’s true legacy? Is he the heroic father of Kenyan democracy, or the ultimate political survivor—the man who touched the nation’s highest ideals but could never fully live them?

Is he the lion of the people, or the vulture of opportunity? History preserves the record—the contradictions, the triumphs, the betrayals.

But it is up to us, the citizens, the scholars, the witnesses, the readers, to wrestle with their meaning.

Waves of change

Perhaps the deeper question we must ask is not only about Raila but about the political culture that produced him.

Why has Kenya, decade after decade, been so enchanted by “strongmen” who promise change but ultimately negotiate only for themselves?

Why does the nation still revolve around personalities instead of institutions?

Why, after so many protests and promises, do we keep returning to the same names, families, and elite bargains?

Raila Odinga’s story is not just his own—it is Kenya’s. It is the story of a country still wrestling with the ghosts of its colonial past, still yearning for leadership that truly serves, still dreaming of a politics where sacrifice is not just performance but principle.

As Kenya stands at the crossroads in the mid-2020s, facing new generations of protest, new waves of discontent, and new demands for accountability, perhaps the time has come to look beyond the Railas—beyond the old lions, beyond the old vultures.

As civic energy pulses through the streets once again, the question remains: will this be the turning point where power truly shifts to the people?

The writer is a History Lecturer & UASU Chapter Trustee, Alupe University-Kenya.