Lessons in push for changes in the Constitution

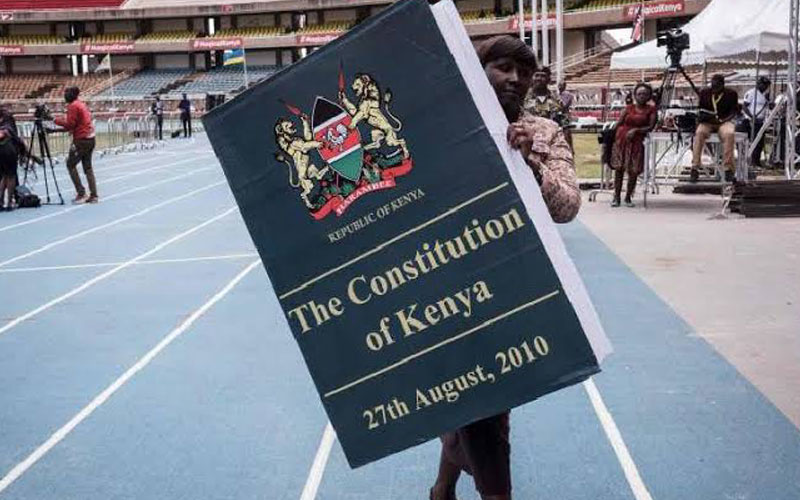

August 20th marked a milestone in Kenya’s nationhood. Millions of citizens spent a fairly good part of the day watching live television as a seven-judge Bench delivered their verdict on the contentious Constitutional Amendment Bill (2020), otherwise known as the Building Bridges Initiative (BBI), that sought to alter the country’s 2010 Constitution.

The judgment stayed the reasons for the High Court’s decision, with six of the seven judges rejecting the proposed changes to the Constitution.

The bench’s main reasons for the rejection included the fact that the political class, or the government for that matter, could not initiate and push such a popular initiative since it was equal to usurping the people’s sovereign power.

The aim of the BBI; an offshoot of the “Handshake” between President Uhuru Kenyatta and ODM leader Raila Odinga.

Its aim was to expand the Executive to accommodate more positions in government, in order to avoid the five-year cycle of volatile elections.

The BBI sought to create, among other positions, the post of Prime Minister, two deputies and leader of the Opposition.

The amended Constitution would also increase the number of seats in Parliament.

But some political analysts said this seemed like a ploy to reward the political old guard in order to maintain the status quo.

Economists were of the view that expansion of the Executive, would overburden the Exchequer which is currently reeling under a huge public wage bill.

It re-awakened the perennial conflict between political expediency and the need for thriftiness in public spending.

The judges, however, avoided the extraneous debate and based their arguments on the veracity of the law, saying that the popular BBI initiative had no legal or constitutional basis.

The judgment has been hailed as a sign of the independence of Kenya’s judiciary, which has occasionally been accused of partisanship in some prominent cases.

Indeed, Kenya’s priorities right now are different, with a high unemployment rate and an economy battered by the Covid-19 pandemic.

While opinion on the constitutional change was divided, many had no problem with the progressive socio-economic clauses, that aimed at enhancing devolution and the equitable sharing of resources according to the population of each County.

BBI proponents had cited the fact that Kenya’s Constitution lacks a “basic structure” and so the question of fundamentally altering the document did not occur.

It is a concept that legal experts seem not to agree whether it exists in the country’s case.

The domino effect of fundamentally changing a Constitution, is usually inimical to the long-term interests of a country since it interferes with the vision of the basic document.

It interferes with the established socio-economic and political structures, which might be too costly in terms of time, finances and human resource.

Political meddling in governance is indeed the bane of many developing countries.

Since politicians in a liberal democratic system are generally myopic, their agenda is inimical to the long-term economic planning and resilience necessary to achieve a high social and economic prosperity for the public good.

Ultimately, the ruling of Kenya’s Court of Appeal shows that something that looks popular may not be necessarily in the people’s best interests.

The popular approach is a major weakness of Western democracy which preaches through the majority rules ideology.

Contrary to politics, the development agenda involves meticulous planning using well trained and experienced technocrats.

Unlike politics which is usually whimsical in nature, development is a game of patience involving the art of the possible in every context.

There is no one-size-fits-all strategy either in politics or economic development, but there are best practices that can be shared by those who have mastered the mastery of differentiation between the two. — The writer comments on international affairs