For great interviews, journalists must prepare well

Did the presidential debates allow journalists and the Kenyan media to shine? The answer is positive since there seems to be a consensus that journalists did not fail.

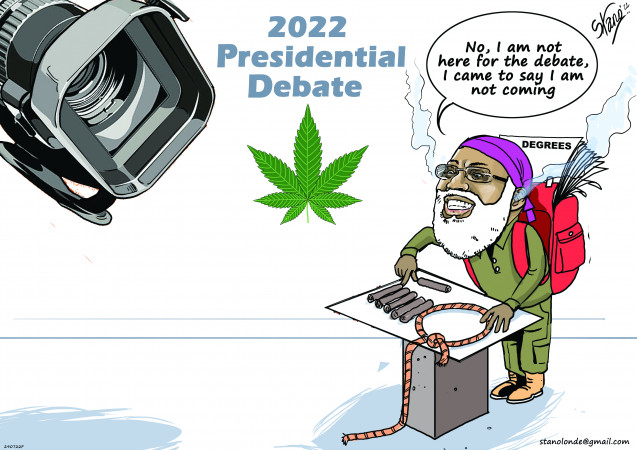

There was a sense of a setback, an anti-climax, when the Azimio-One Kenya Alliance presidential candidate declined to show up for the debate. But the performance of the journalists detailed to host what was billed to be a debate compensated for the no-show.

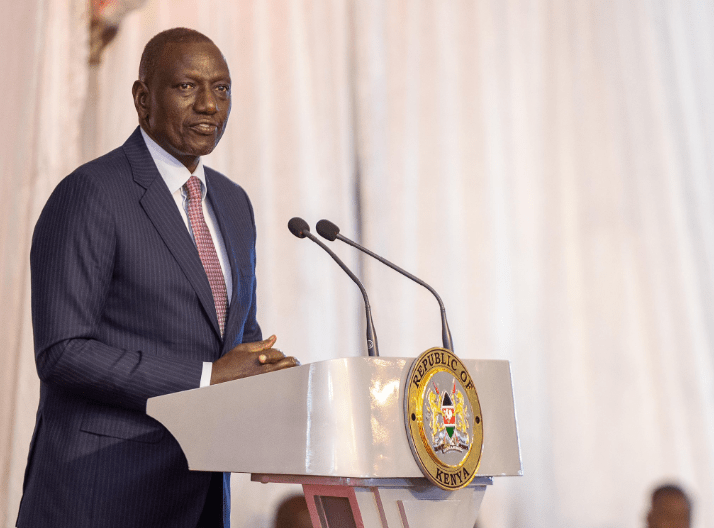

For those who missed the show, it was no longer a debate, but an interview with Deputy President William Ruto standing alone at the lectern with all eyes and cameras trained on him. It was an opportunity for him to dominate the airwaves uninterrupted for 90 minutes.

Going by the past, and how these interviews have panned out the assumption is that Ruto would have rammed down the broadcast tube telling his story. But soon it became obvious that the two journalists had a different script.

What made the difference seems to have been simple – preparation. The journalists were deliberate in their preparation. They seemed to have set up their questions, anticipated responses and prepared follow-up questions.

So when their subject provided the generalised rehearsed responses, the journalists simply pressed on with the follow-up questions for which it seems the subject was not prepared.

The second asset for the journalists was their demeanour. They did not come through like gladiators prepared to hound their victims. Rather, it was a calm almost tame demeanour that served the questions in a cold and calculated manner. It was a genuine desire to probe further to get to the core of the issues.

It is up to the public to judge how the candidate performed – whether the answers were satisfactory or whether from the way the subject answered the questions they could read the subtext. But this is about the journalists and how they went about their work, and the fact that they did their homework. The performance of the two was not isolated. Nearly a fortnight earlier at the Bomas of Kenya, the IEBC had assembled journalists for a session of talking to the press.

What stood out from that interview was, again, the performance of one journalist who appeared to have prepared for the interview and served one question for which the panel of both the Chairman and CEO of IEBC did not seem prepared.

It was a simple question. Did IEBC do a background check before bringing one of their service providers that were going to play a critical role in the elections on board? Did they know that service provider’s records in Uganda, Venezuela, in the Philippines and other electoral assignments?

The chairman passed the question over to his CEO who appeared to have no clue and fumbled times over. At some point, he almost appeared to accuse the journalist of having done his homework and eventually asked the journalist to go and look for the service providers and ask them to respond to the question.

IEBC, at that point, did not inspire confidence. It left one wondering whether the team at IEBC were taking their work seriously at all. Again, this is about how journalists are doing their job.

It is the task of journalists to probe their subjects and bring to the public the full story. Those who have the story are usually bent on telling journalists only the part of the story that is palatable, but journalism must probe further.

To do a good job reporters would need the background support of a team of researchers, a clear theme of the interview and the discipline to remain on the subject and probe until the full story comes out. It may be argued that these incidences of journalists probing their sources in detail are isolated, but at least it is a good indicator of what Kenyan journalists are capable of – a professional detailed interview. It is the substance needed to play a watchdog role.

—The writer is the dean, School of Communication, Daystar University