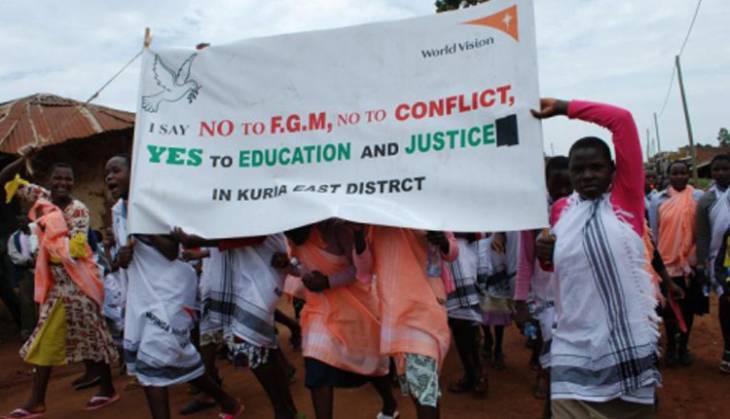

FGM is a manifestation of entrenched inequality

Doris Kathia

Female genital mutilation (FGM) is globally recognised as a violation of human rights globally.

The vice subjects women to long-term physical, psychological and social problems. This poses a danger to the current and future generation of girls and women.

Despite this, over 200 million girls worlwide are at risk of undergoing the harmful practice every year.

In Kenya around four million women and girls have been subjected to FGM. It is estimated 574,000 girls are at risk of undergoing FGM between now and 2030 if urgent action is taken to prevent it.

The vice is a manifestation of entrenched gender inequality. It is rooted in social norms within a frame of psycho-sexual and social reasons like control of women’s sexuality and family honour which is enforced by community mechanisms.

It is time to act fast in addressing the structures and gender norms that perpetuate the practice.

In counties where FGM is rampant, the county governments must work closely with grassroots organisations and communities to develop strategies for challenging the social norms and behaviours that drive the practice.

Communities that practice FGM consider it as part of raising a girl and a way to prepare her for adulthood and marriage.

FGM and child marriage are often intertwined. When a girl undergoes FGM, she is often expected to get married shortly after.

Additionally, girls and women who are uncut are often excluded from wider social events within the community and more so subjected to stigma and being ostracised by family and the community.

Male involvement is a crucial aspect in eradication of the vice. Some communities believe that girls and women who have undergone the ritual are a source of wealth to their families through marriage.

This is not the case for girls and women who do not undergo FGM, since this is deemed to weaken traditional family structures and draw women into the labor market, which changes their economic and social roles.

There are various challenges that facilitate FGM in many of these communities. For instance, girls and women have limitations with education and this have a correlation with FGM rates. In many areas, girls are withdrawn from school and undergo FGM in preparation for marriage.

The practice is also seen as a marker of ethnic identity that can generate deep resistance to change efforts especially due to shared norms concerning marriageability, sexuality and other values.

Kenya has ratified several international documents that have become part of the law as stated in Article 2 of the Constitution and the enactment of the Prohibition of Female Genital Mutilation Act, 2011.

This law provides a structure for public engagement and advocacy for accelerating the eradication of FGM. The Children’s Act, 2001 also criminalises the subjecting of children to harmful cultural practices.

The Protection Against Domestic Violence Act, 2015, classifies FGM as violence and provides for protective measures for survivors and victims of domestic violence.

To help girls at risk of FGM or who have undergone the procedure to access justice, there is need for continuous strengthening coordination and cooperation between child protection bodies, the police, prosecutors and courts.

There is need to establish powerful community surveillance mechanisms as a crucial means to ensure the protection of at-risk girls and women, while collaboration between community leaders and law enforcement officers will help curb emerging trends and prevent cross-border FGM.

There is also need to strengthen collaboration among civil society organisations working to combat harmful practices, with others in allied areas such as emergency-related programmes, alternative care, social protection and education.

— The writer is a sexual and reproductive health and rights advocate at Network for Adolescents and Youth of Africa