Adapt literature by Kenyan public figures in studies

By Emeka Mayaka, January 5, 2024We owe Prof Godwin Siundu a book. An old and dusty copy of Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks which I found in the most unlikely of places. In a heap of old shoes at a shed owned by a shoe shine on a notorious Nairobi street.

The owner does not know its value so he readily offers it to me.

He tells me that a street urchin solid it to him for Sh20 and that he whiles away his idle time reading it. Details therein show that the professor of literature must have bought it from some university library in London.

“A strange haunting mélange of analysis, revolutionary manifesto, metaphysics, prose poetry and literary criticism –and yet the nakedest of human cries,” says the Newsweek in a review of the classic.

“A reasoned, explosive and an important book centred on the identity problem of the black man by the author of a classic study of racism and colonialism, Wretched of the Earth,” says another reviewer.

Second encounter. Our estate wag challenges me to a walk in the night to nearby pub to watch football.

Pulling a tattered Shakespeare’s Hamlet from his arm bits, he lectures me on what he considers poor reading habits by Kenyans and demanded to know what book I was reading. I told him that I had just devoured Aden Duale’s For the Record.

Then he launched a tirade claiming Kenyans were afraid of interacting with sciences, classic literature, anthropology, astronomy, religion and technology. The issue is debatable but our only bit of convergence was our leaders–from business, media, politics and arts– should document their experiences.

It also evoked a sense of guilt by yours truly and a colleague share for failing to take up a challenge to document the life of the late Maasai supremo, Mzee William ole Ntimama.

Despite not having stepped inside a classroom, Ntimama was self- educated and built a body of knowledge for transmission to generations. In a column we were doing with public intellectual Julius Sigei, the then aging Ntimama regaled us with his reading habits. At, 85, he told us that his reading had slowed down a bit.

“I now read newspapers and one or two books. I read late into the night. I am reading a little interesting book I picked in New York. It has this debate between Churchill and (Clement) Attlee. They are arguing whether India should be granted self-determination. Attlee is for the idea of decolonisation whereas Churchill asserts that the sun will never set on the British Empire,” he told The Conversations with Book Lovers column.

We then asked him why he had not penned a memoir.

“My family and friends in Europe and America, who concur that my 40-year unbroken record in leadership, have advised me to record my life. I have not settled on writers. I am inviting you to write the book because you have access to vast information on me from your library.”

Regrettably, we did not take the offer. There has been a consistent call for those in positions of leadership to document their exploits in books.

This is the way a society expands the realms and repertoire of national knowledge, informs the young and enriches decision making.

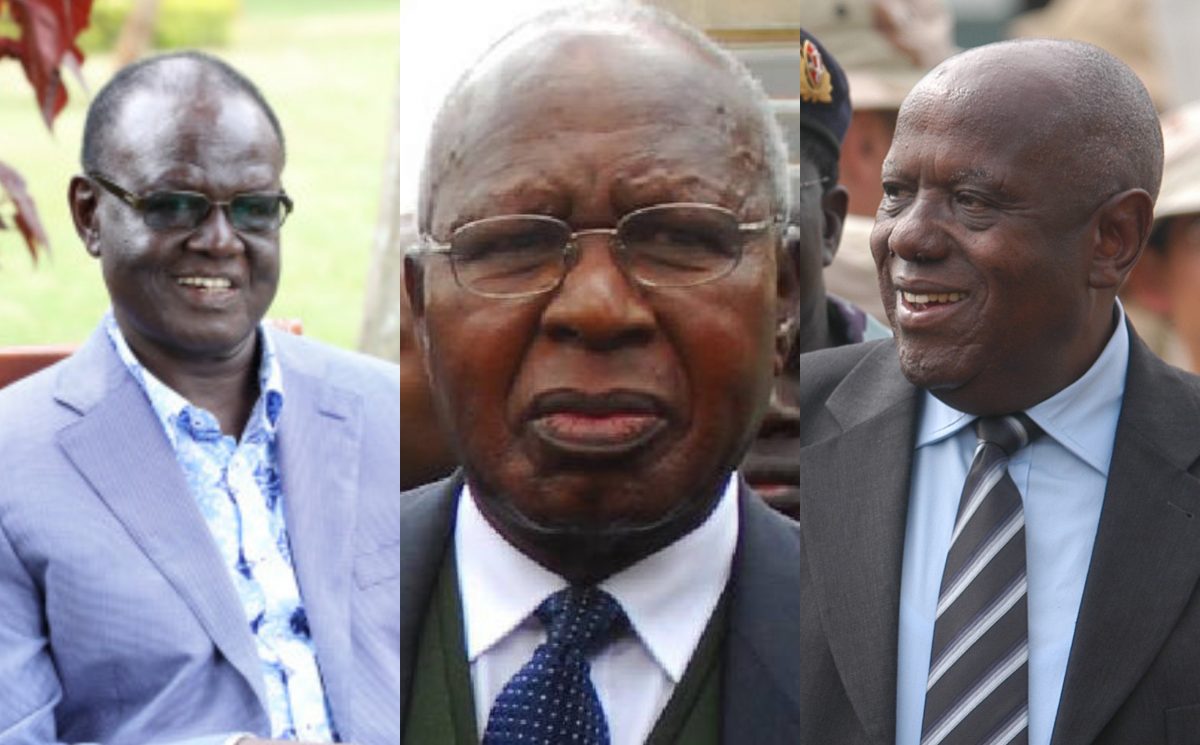

Jaramogi, Bildad Kaggia, Tom Mboya, Simeon Nyachae, Njenga Karume, Kiraitu Murungi, Wangari Maathai, Kalonzo Musyoka, David Musila, Musalia Mudavadi, Anyang’ Nyong’o, Kivutha Kibwana, Francis Muthaura, Duale and other public figures have put their imprints on discourses around politics of power, colonialism, law, liberty, conservation and human rights.

The major concern, however, is whether these contributions have been mainstreamed in our school syllabuses.

It is high time we mainstream the efforts of our later-day leaders and theorists in syllabuses in order to relay recent experiences, silences and histories?

— The writer, a founder of the Kenyan Speechwriters Clinic, is thepolitical editor, People Daily.

emekamayaka@gmail.com