Think tank urges State to relook at ‘inefficient’ silos

A local economics think tank has recommended that the government should consider adopting a virtual cash grain reserve instead of storing stocks to end perennial food shortages in Kenya.

The Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA) reckons that having a virtual grain cash reserve will be more efficient, as it will enable the State to buy grain, especially maize when the commodity is required. However, certain preconditions must be met, says the think tank.

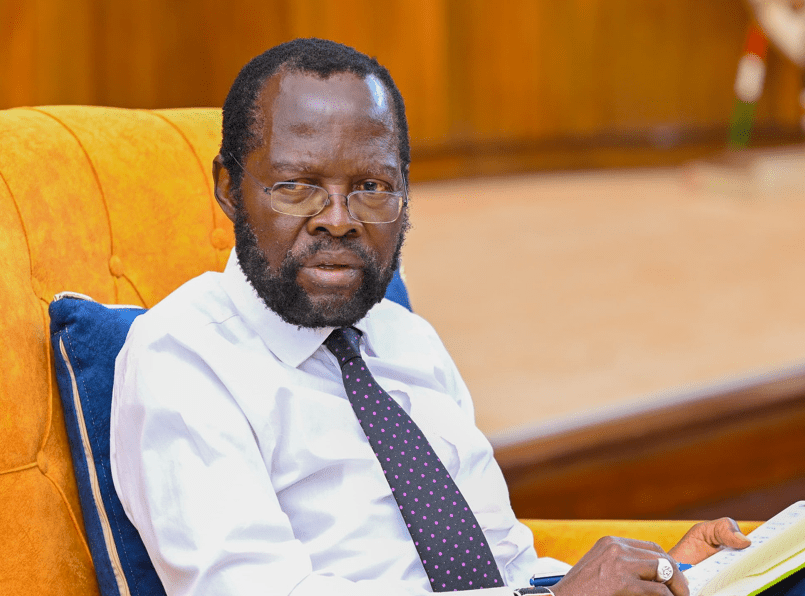

From experience over the years, the IEA Chief Executive Officer (CEO) Kwame Owino notes that storing the grain has proven inefficient, with lots of maize going to waste in silos and stores.

“We think at the Institute of Economic Affairs, [that] it is an efficient way of spending public money. Why, because what you need is a cash reserve which can be virtualised,” Owino said during an interview with the Business Hub on Tuesday.

New grain reserve model

The institute said whether it is Genetically Modified or organic maize, Kenya’s problem is that of demand and hence the need to streamline the supply intervention, which can be achieved by the introduction of the virtual grain cash reserve model.

“You have seen every year [that] a lot of that grain gets messed up and spoiled. So instead of keeping physical stocks, you can actually keep it in a virtual reserve in terms of cash… [and] simply releasing the cash that is used to buy the grain instead of keeping physical stocks,” he said.

According to Owino, there are a lot of ships loaded with maize, wheat and rice floating in the high seas, and “as soon as they see a country that has shocks, they move close to your borders.”

“Let the guys who do the trading do it properly. They trade millions of tonnes. If they know that the government of Kenya has a bank account and you write them that cheque, they will appear in two weeks or less,” he said.

“So, the idea that we must have stocks in big stores to assure the world or each other that we will not starve is a sixteenth-century idea about how to ensure food security. We need to have a change of mind.”

This idea comes amid a storm over the importation of 10 million bags of Genetically Modified maize and a similar amount of organic maize to alleviate hunger caused by the prolonged drought, the worst in 40 years, even as farmers in Rift Valley and Western Kenya regions have harvested between 30 and 40 million bags, enough to feed the country.

It also begs the question of what would become of the National Cereals and Produce Board’s (NCPB) 118 grain Silos located across Kenya with a total storage capacity of 1,842,345 metric tons.

These storage facilities comprise conventional store and silos complexes, with storage services offered at competitive rates. In 2020, NCPB opened the facility for farmers to dry and store maize at between Sh20 and Sh40 per unit drop of moisture content. Analysts have also blamed Kenya’s lack of improper food market systems as a major reason why some parts of the country continue to suffer every time there is drought.

According to the East African Grain Council (EAGC) Chief Executive Officer Gerald Masila, poor market systems have seen high-production areas struggle with food surplus, while low-production areas, especially the arid, suffer hunger during dry seasons.

This lack of proper local market linkage planning has led to knee-jerk reactions from the Government, which under pressure to satisfy grain demands, resorted to importations through duty waivers to ease the pressure, especially on maize flour prices.

In 2018, duty was waived on the commodity, to allow traders to import 77,500 metric tons from Uganda and Tanzania after harvests were dampened by drought and fall armyworms.

As late as August this year, immediate former National Treasury Cabinet Secretary (CS) Ukur Yatani opened a three months window that lapsed in September 2022 for merchants to import 540,000 metric tons of maize.