This year’s United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP29) opened yesterday in Baku, Azerbaijan, with adaptation and finance on the agenda.

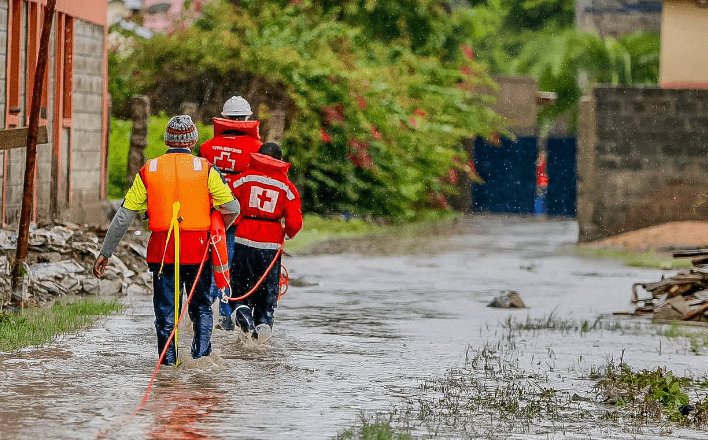

Unep’s Adaptation Gap Report 2024: Come Hell and High Water, released last week, finds that nations must dramatically increase climate adaptation efforts, starting with a commitment to act on finance at COP29.

The climate finance landscape is expected to shift significantly at the conference with the establishment of the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG).

The NCGQ aims to replace the existing $100 billion annual climate finance target set in 2009 with a more ambitious goal that considers current climate vulnerabilities and increased funding needs in developing countries. Projections suggest that developing economies will need around $1.1 trillion by 2025, rising to $1.8 trillion by 2030, with the private sector expected to play a more substantial role than before.

At the Paris COP21 in 2015, in accordance with Article 9 paragraph 3 of the Paris Agreement, developed countries decided on the intention to continue their existing collective mobilisation goal through 2025 in the context of meaningful mitigation actions and transparency on implementation.

It was also agreed that before the 2025 climate conference, parties to the Paris Agreement would set a new collective quantified goal from a floor of $100 billion per year, taking into account the needs and priorities of developing countries.

The ad hoc work programme on the NCQG commenced at the beginning of 2022 and concludes at COP29 in Baku. The global context has changed considerably since the $100 billion goal was set in 2009.

Climate-related initiatives in both the public and private finance sectors have significantly expanded, alongside an overall increase in global climate efforts.

Conversely, climate impacts and vulnerabilities to such impacts have increased across geographies, along with economic pressures, such as growing debt burdens in many developing countries, according to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)/International Energy Agency Climate Change Expert Group.

This evolving context makes the process of establishing a new goal that is both ambitious and achievable even more complex, the experts note.

Last week, UN Conference on Trade and Development published its report on the quantitative and qualitative elements of the NCQG.

The report conveys a strong message that global climate finance needs a boost in both quality and quantity to address developing economies’ needs for a just transition towards sustainability and resilience.

The report modelled projections using the UN Global Policy Model, a tool for investigating policy scenarios for the world economy. Based on these projections, developing countries require around $1.1 trillion for climate finance from 2025, rising to around $1.8 trillion by 2030.

Provided that key coordination measures that can better support developing countries are implemented at the international level, developing countries are expected to contribute around $0.89 trillion in 2025, rising to $1.46 trillion by 2030.

This implies an NCQG target of around 1.5 percent of developed countries’ GDP. From the assessment, ultimately the goal of the NCQG must be to transform the climate finance landscape and herald a new era of mutual trust, cooperation and climate action.

Mobilising private finance will be therefore a key consideration of the NCQGs during the COP29 talks. The UN Framework Convention on Climate Change says private finance mobilisation in relation to the $100 billion goal has fallen short of expectations.

The OECD notes that private finance mobilised reached $21.9 billion in 2022.

— The writer comments on climate change; [email protected]