How SHOFCO is addressing teenage pregnancy in Mathare

Rejection, stigma, loss of education, selfdiscrimination and poverty define the life of hundreds of teen mothers living in lowcost stretch of shanties along the Mathare Valley in Nairobi.

The low-settlement area is a picture of misery, revealing low quality of life that goes against the Sustainable Development Goal goal 1, which places health as a booster of quality of life, and which commits to end poverty in all its forms everywhere.

Article 43 (1) (a) of the Constitution provides that every person has the right to the highest attainable standard of health. But this is not the case for Nancy Kareke, a 17-year-old teen mother. She remembers her journey since she conceived.

The memory of her mother looking at her and expressing her emotional fatigue haunts her till today.

“In 2015, I became expectant. Darkness engulfed me,” she said during an interview at the Shining Hope for Communities (SHOFCO) centre in Mathare.

She was at loss of words to explain this to her mother who was also expectant. Nancy was in Form Two when she found out she was four months pregnant.

Failed attempts

Rejection by the young father-to-be who was also a student immediately followed and failure of the community to be accommodative devastated Nancy.

“I was so hurt; I battled with thoughts and attempts to abort the baby. I sought audience with the boy’s parents and gave them a chronology of events leading up to the pregnancy. They dismissed me as a liar who wanted to frame their son,” Nancy says.

She soon stopped going to school, without telling her parents about it and about the pregnancy. What occupied her mind most was how to terminate the pregnancy, and many options were at her disposal.

They all didn’t bear fruit.

“I went to one of my best friends to seek help on how to terminate it, but she didn’t have a clue,” she narrates. On the second attempt, she swallowed some family planning pills, but that too didn’t help. She tried th third time.

“I had heard of the potency in tea leaves. I boiled, it didn’t work,” she explains.

After hitting one brick wall after another, her next mission was to reach out to her mother through a friend. She had premeditated her mother’s reaction.

She had told the friend sent. that she did not want to see her mother. Fortunately, her father asked her to go home, but she had already settled in with .

“I delivered a baby boy in 2018, and named him after my father,” she says. Nancy vividly remembers the journey towards her pregnancy.

“I was used to cloth during my menses when other girls were using pads. My boyfriend stepped in and gave me money for pads. Little did I know this was a sure way of becoming a young mother,” she says.

She didn’t know anything to do with contraceptives, leave alone the morning after pill. At some point during her pregnancy, Nancy had contemplated suicide.

“I swallowed 20 Panadols, assuming it’s an overdose, but I only felt dizzy and was taken to hospital, where I was treated and discharged for counselling,” she says, adding that three of her peers are also pregnant and battling depression.

Nancy was fortunate to have someone to help her overcome the stress in form of her aunt, who provided psychosocial support and SHOFCO social workers.

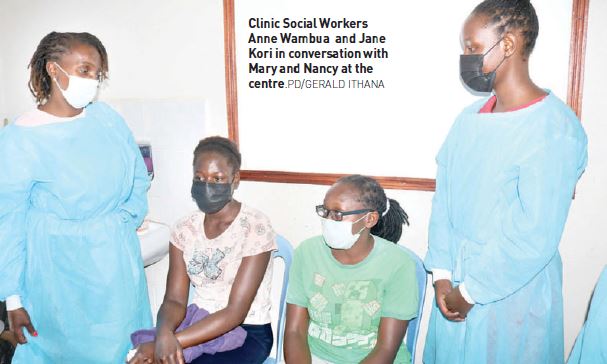

Anne Wambua and Jane Kori, social workers at SHOFCO, say in just one month, they attend to 15 to 20 teen mums. Mary Atieno Otieno, 24, is one of them. She got pregnant immediately she finished her Kenya Certificate of Secondary Education (KCSE) in 2016.

“It was a huge disappointment for me and my family because I am the first born and there was huge expectation from me,” she says.

She wanted to continue with her studies beyond secondary school to get employed so that she can support her mother and three siblings.

All was fine the first three months of her pregnancy, until the young father broke up with her.

“I was forced to care for the pregnancy alone. It was stressful,” she said. Being the first pregnancy, she didn’t even know basic things about childcare.

Just like Nancy, she had also contemplated terminating the pregnancy several times, but her friends and mother encouraged her to give birth.

“I was so depressed, imagining how to start the life of parenthood at 19,” she

notes. Buying clothes for the child and those other aspects of bringing up a baby were a heavy burden for the girl. What hurts most, as revealed at the interview is the way she conceived her second baby, whom she delivered in 2019.

“I didn’t know what happened as I was on a long-term family planning method,” Mary says.

Continuous teasing from her peers over her weight pushed her to do a pregnancy test.

“It was a shock. My first baby was two years old. I didn’t have a job or money, was still staying with my parents and was not in good terms with the father of my two babies,” she adds, noting that on several occasions she contemplated suicide.

“Even my mother was shocked, and couldn’t believe it. She sided with my babies’ father, who said the last born could not be his,” she narrates. From then on she has never heard of him.

He never even calls to find out about the children. Wambua, who has been at the centre for last four years, says it has been quite a journey supporting numerous teen mums with various psychological and social challenges. “We have managed, however, to reform some and linked them with organisations for capacity building. Some are doing great,” she says.

Data at the Centre shows that in a week, five to six young girls present with pregnancy. One of the most common questions mothers of the poor girls asked is ‘why did you have a baby when we still have so many problems at home?”

“It is as if they are blaming them but we have been instrumental in helping parents come to terms with the situation, telling them to embrace, love, and encourage their girls to push on with life positively,” she adds.

She points out that girls have had it rough because even the society uses them as examples when talking to the younger ones; ‘Don’t be like Mary. You see the way she became pregnant and bore children when still young. Don’t be like them.” The enduring stigma has affected their mental status.

“They have suffered depression, at times locking themselves in the rooms, and don’t want to come out. They could cry alone in the house the whole day, and some contemplated suicide,” she notes.

However, she is happy to point out that the psychosocial efforts are bearing fruit.

“We have managed to turn some of them around, engaging them in various community activities,” Wambua states.

Sometimes unplanned pregnancies come about because of lack of access to contraceptives. Kori said they mobilise the teens and engage them with family planning sensitisation programmes, bearing in mind that awareness has been low.

“Due to the mobilisation, quite a big number of young girls have embraced family planning, and we have also involved the chiefs and assistants, Nyumba Kumi initiative and community leaders so that when we bring the mobilisation they are not surprised,” she chips in.

Majority of the young girls are now taking long term methods, but it is different for the young men who don’t come for condoms.

“We pack them in brown paper and staple them for their girlfriends take to them,” she says, expressing sadness that even as the latex commodities go like hot cakes, pregnancies are still happening.

Emma Ingaiza, the director of health at the Centre says there is still so much work to do to turn around the situation. One of them is to take reproductive health to the lower Primary school.

“Four out of five adolescents who conceive and become pregnant, face almost total rejection in their families and are left stressed. The worst is that we find them when it is too late,” she says, calling for more reproductive health talks to ensure such cases are presented early.