My visit to Naimene Enkiyo, the sacred forest in Maaland

Going to the sacred Naimene Enkiyo (lost child) forest, which Loita clan of the Maasai hold so dear, is interesting and needs a lot of patience for whoever is visiting for the first time.

The journey of about 175km starts from Narok town, where two G-touring vehicles ply the route.

This is a new thing; years back, there were no Public Service Vehicles (PSVs) and people relied on private vehicles for the journey.

My trip to Entasekera started at 4pm. After over 90km later, we stopped at Narosura trading centre, in what the driver said was for refreshment.

However, travellers know it was mandatory for any vehicle on this route to stop here, for about an hour or so, for the driver to get clearance from Laibons to continue with the journey.

Seek permission

They say anyone denied this permission never reaches Entasekera, Olorte and the larger Loita area without hitches, including frequent vehicle breakdowns or attacks by bees.

“We cannot leave Narok and go straight to Entasekera without stopping at Narosura. It has never happened.

We have to know how the escarpment is and inform wazee (Laibons) we are on the way.

Please, don’t ask more questions,” Leboo Sonkori, the driver told me when I curiously asked.

We left Narosura some minutes past 6pm and after an hour, we arrived at Entasekera, the last point for all PSVs.

I met John Sambino, the man who was to connect me with the Laibons to seek permission to enter the sacred forest.

The following morning, Sambino and I, set off to a senior Laibon’s house about 5km away. Sambino, I was informed was an age-set chief.

Upon telling him my mission of finding out how the Loita clan conserved and managed the Naimene Enkiyo forest, Laibon Joseph Mokombo, 91, looked at me with suspicion. It took a lot of convincing by the two gentlemen, for him to indulge me.

He sent for another Laibon, Kone ole Senteu, who luckily knew me from the time I first arrived in Narok in 1993.

I explained that I wanted to highlight the good work the people of the area do in conserving the forest and without hesitation, he asked Mokombo to let me venture into it but it was not without a warning.

“Go and write good things about us. If you have a bad motive, you will never go back alive. Or you will be unable to hold a pen to write anything about us,” he said.

My hosts told me in early 1990s, when the defunct Narok county council wanted to forcefully take over the management of the 74,131-acre forest, a reporter of a local daily who had gone to file a feature favourable the council, was unable to do the assignment because Laibons stood in his way.

“A dark cloud and fog covered the forest for all the days he was here. He left confused without even interviewing anybody or taking pictures. Elders knew he was not up to any good,” said Sambino.

He further said the council failed to take over the forest because of the work of laibonis.

“Even the surveying of the forest didn’t take place. Whenever surveyors came, they couldn’t do their work.

Once senior council officers were forced to flee, after pythons were dispatched to them the moment they set foot in the forest,” he said.

Locals believe their gods reside in the forest.

Deep inside the forest, I watched with ease various birds species including the wild parrots and from a safe distance, herds of elephants.

The forest of the lost child is one of few well protected community forests in the country.

It got its name from a local Maa legend about a young girl, who was tending her family’s livestock, some of which strayed into the forest.

She followed to retrieve them but never came out of the forest even after the calves found their way home.

Located in Narok South, along the Kenya-Tanzania border, the Maasai of both countries annually pay pilgrimage to it, to perform customary obligations including appeasing their gods, especially during droughts and after deaths of prominent personalities from the community.

Way before people started settling near it, locals say the Laibon performed a ceremony at Entasekera to curse anyone who would disturb its natural state.

“This forest where our child got lost is sacred to us. We only venture into it whenever there are ceremonies or when looking for herbs,” says Raphael Ololpapit, a Laibon.

Wildlife poaching

Ololpapit, 95, who is one of the trustees of the forest, says they have succeeded to keep loggers and poachers at bay.

“You cannot enter the forest even to fetch a tooth pick or firewood without elders’ approval lest you are cursed. We are also working with youth groups and Community Forest Associations (CFAs), in its conservation,” he says.

The area, inhabited by about 3,000 members of the larger Loita clan suffers poor infrastructure. There are no good roads or proper mobile telephony coverage. Elders say lack of good roads is a blessing.

“If these roads were good, logging and poaching would have been the order of the day,” says John Samberu.

Mark Karbolo, formerly the manager of Loita Ilkerin Integrated Project, which is tasked with preserving the forest, says several investors have approached the community to set up tourist facilities, but their requests have been turned down.

“The forest is good and strategically situated for setting up of lodges and camps. Its flora and fauna is unmatchable.

In fact, if opened up, it will dwarf the world famed Masai Mara Game Reserve.

Three big rivers including Sand River that drain into Mara River and Lake Natron in Tanzania emanate from the forest.

Locals and elders have for many years resisted temptations to give it away s because of its importance” he says.

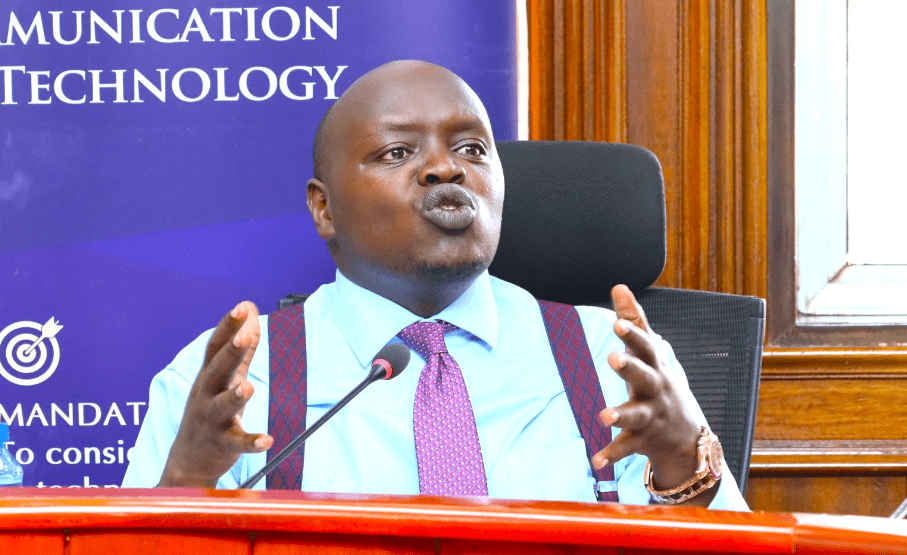

Mwai Muraguri, the Narok County Kenya Forest Service Ecosystem Conservator, says Naimene Enkiyo is the only community forest that is well managed in Narok.

“We are providing technical support to them and also in policing. The involvement of elders is encouraging,” says Muraguri.

Paula Kahumbu, Wildlife Direct chief executive says the forest is one of the remnants of Kenya’s indigenous of the larger Mau ecosystem.

“We must do whatever it takes to save it and the culture that has defended it for centuries. The government must recognise and protect it ,” she says.