Details of South Sudan’s unity deal between Salva Kiir and Riek Machar

Former South Sudanese rebel leader Riek Machar has been sworn in as first vice-president, sealing a peace deal aimed at ending six years of civil war.

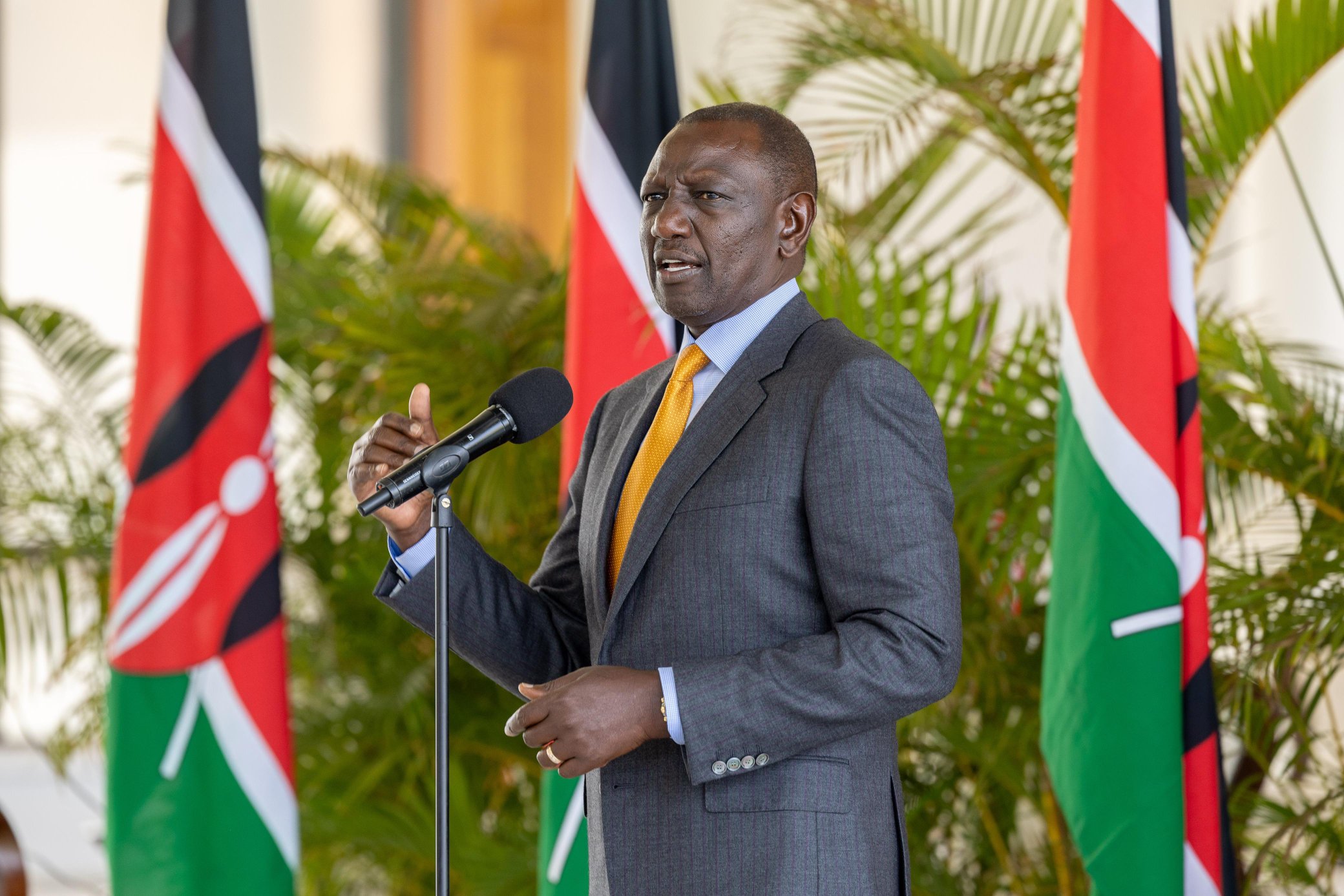

President Salva Kiir witnessed the moment at a ceremony at the State House in the capital, Juba.

It is hoped that the new unity government will bring an end to the conflict that has killed about 400,000 people and displaced millions.

However, previous deals were widely heralded only to fall apart.

Saturday’s ceremony took place just before the deadline for an agreement expired.

“For the people of South Sudan, I want to assure you that we will work together to end your suffering,” Mr Machar said after taking the oath.

He then embraced and shook hands with President Kiir.

“We must forgive one another and reconcile,” said Mr Kiir. “I also appeal to the people of Dinka and Nuer (rival ethnic groups) to forgive one another.”

Also present at the ceremony was the leader of Sudan, General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan.

Three other vice-presidents were also sworn in including Rebecca Garang, the widow of South Sudan’s founding father, John Garang.

Under the agreement, the current cabinet has been dissolved to make way for more opposition members.

Correspondents say some issues remain unresolved including power-sharing and the integration of rebel fighters, but the two sides have agreed to form a government and address other matters later.

The deal was announced hours after the UN released a damning report accusing both sides of deliberately starving civilians during their struggle for power.

What’s the significance of the agreement?

President Kiir has expressed hope that the transitional three-year period will pave the way for refugees and internally displaced people to return to their homes.

In addition to those killed or displaced, many others have been pushed to the brink of starvation and faced untold suffering.

If the deal holds, it could herald a fresh start in the world’s newest country.

What is the fighting about?

South Sudan became an independent state from Sudan in 2011, marking the end of a long-running civil war. But it did not take long for the promise of peace to crumble.

Just two years after independence, the country returned to violent conflict after President Kiir sacked Machar, then the deputy president in December 2013.

President Kiir had accused Mr Machar of plotting a coup to overthrow him, which Mr Machar denied.

While the war had political origins, it also has ethnic undertones and is based on power dynamics.

The Dinka and Nuer, South Sudan’s two largest ethnic groups, which the two leaders belong to, have been accused of targeting each other in the war, with atrocities committed by both sides.

Why has it been so hard to strike a deal?

Parties had been unable or unwilling to agree on the terms for the formation of a transitional government, in line with the revitalised peace agreement of 2018.

The deal was supposed to have been finalised by May 2019 but was postponed twice – the latest deadline being 22 February.

The conflict has pushed the country into a catastrophic humanitarian crisis.

Despite the situation, it has been difficult for the parties to reach and maintain a peace deal that could stabilise the country.

The two main leaders have a mutual distrust of each other and there has not been a cordial working relationship since President Kiir fired Mr Machar in 2013.

Mr Machar has never returned permanently to the capital, Juba, fearing for his safety. He fled the country when his forces were engaged in fierce clashes with government troops as the 2016 peace agreement collapsed.

Does the deal guarantee lasting peace?

There are certainly no guarantees.

More than 10 agreements and ceasefires have been reached since the two leaders fell out in 2013, and their inability to sustain any deal, including on power-sharing, has been at the heart of the conflict.

Peter Adwok Nyaba, an activist and former minister in South Sudan, says in a 2019 advisory that the agreement does not fully address the conflict elements of ethnic nationalism, power struggles and weak institutions of governance, which he says remain alive despite the deal.

“This is a typical vicious circle: poverty-conflict-peace lack of development then conflict,” he says.