A property seller recently called the buyer to inquire if the man had read their agreement before they could consummate the contract.

“What is your problem?” the buyer, who was on loudspeaker, asked irritably. “I have paid you Sh2 million and you are asking me to read a document?”

What followed was a series of unpleasant exchanges, but the seller kept repeating his refrain: “Please read the document. Please read the document.”

It turned out it was a nine-page contract, but efforts to get the buyer to read it — presumably for his own good before putting pen to paper — turned out to be an exercise in futility.

The KenyaDemographic and Health Survey, (KDHS) 2022, published this week, says anyone who has attended higher than secondary school is literate. One is also considered literate if one can read part of or an entire sentence.

Whereas literacy denotes ability to read and write, it does not in any way connote a willingness to do so. That is why celebrated American author Mark Twain observed wryly that “a person who won’t read has no advantage over one who can’t read”.

This, unfortunately, is the unenviable position that many Kenyans find themselves in, including the man who was being forced to read a contract regarding a Sh2 million payment he had made without signing any document.

In Kenya, according to the KDHS, 91 per cent of women and 94 per cent of men are literate. At least 19 per cent of the women who were interviewed for the survey and 21 per cent of the men had more than secondary school education. That means if they wanted to read, they could.

But, according to Kithusi Mulonzya, the Managing Director of The One Planet Publishing and Media Services, one of the leading book publishing firms in Kenya, pre-teens and teenagers read more than adults.

“At One Planet, we have witnessed more sales at lower secondary (Form One and Two), and they are buying more of the novel and novella than the other genres,” he told People Daily.

Lack of publishers

Generally, he said, Kenyan publishers sell more leisure reading books in upper primary than in any other level of the education system.

Whereas this segment has been thriving and publishers keep churning out leisure reading materials to meet their needs, the same cannot be said of lower primary and adults leisure reading segments. For instance, one of the leading publishers of children’s stories, Phoenix Publishers, has not paid royalties to authors in more than 10 years and is currently under receivership.

And in the adult segment, there is virtually no publisher in this niche, with authors targeting adult readers resorting to self-publishing.

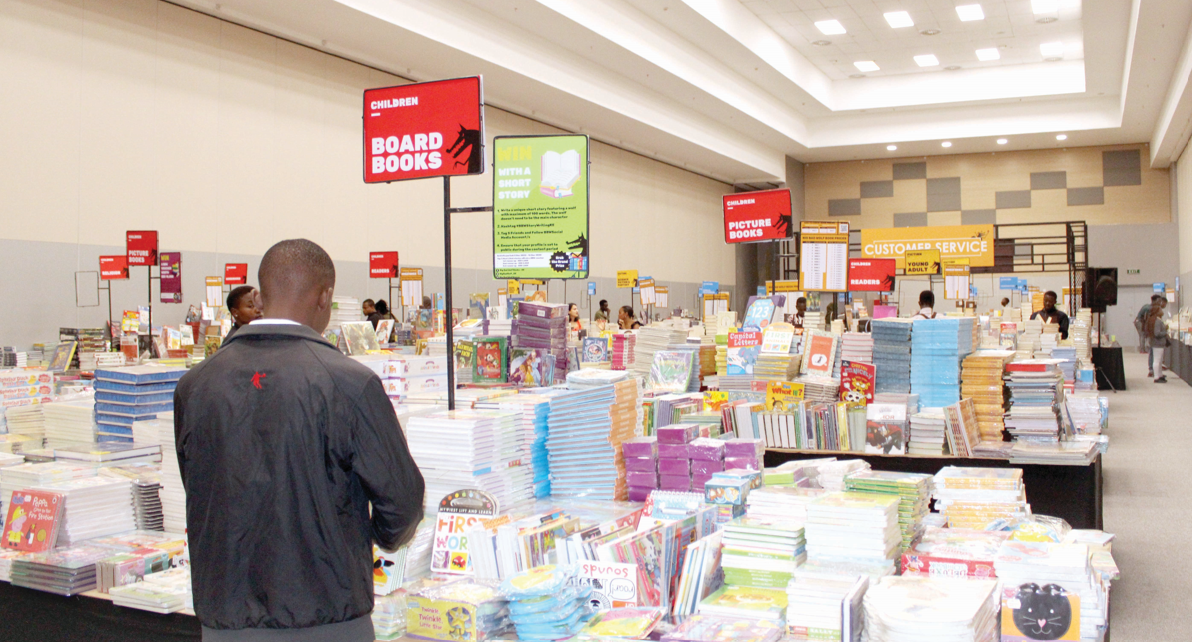

According to Abdullahi Bulle, the founder of Nuria Bookstore in Nairobi, the last time he counted, there were 650 self-published authors seeking to distribute their books through his start-up.

“Adults are more likely to buy story books for their children,” said Bulle. “But when they buy for themselves, they choose autobiographies, fiction and self-help books in that order.” Among the very young readers, colouring and educational books are second and third in terms of demand.

According to the Demographic Survey, which somewhat bears out the observations of the two market leaders, only six per cent of women and three per cent of men aged between 15 and 49 have never attended school. Which means a vast majority has been to school and interacted with academic and leisure reading materials. So, why do they not continue reading into adulthood?

Three emerging factors

Three factors emerge from the government data published by the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. The first has everything to do with gender. There are fewer women with access to education — and hence reading materials — compared to men. Women in rural areas have even lower chances of finding a book compared to their counterparts in urban areas. And women in poor families are far less likely to get a book compared to their counterparts from the richest families. Only one per cent of women from wealthy families had no education — which is negligible in real terms.

The second is where one lives. Generally, men and women in rural areas have less access to education and books compared to their counterparts in urban areas, where public and school libraries abound and the distances between home to school are negligible compared to rural areas.

The third is, of course, wealth. About three in 10 families in Kenya cannot afford all three meals a day. That means, for them, entertaining the idea of reading is already a luxury.

As a rule, access to education and reading materials increases with family wealth. But are they wealthy because they read or do they read because they are wealthy?

Anyway, the three gaps, can, however, be bridged by harnessing technology and through public and private initiatives. For instance, the Kenya National Library Services, which offers unlimited access to reading materials for a small daily fee, has embarked on an ambitious project to make available all books published in Kenya in a digital bookshop. Because these titles will be affordably priced, they will only remain in a buyer’s gadget for 365 days, after which access to the book will expire.

Mobile phones

Given that the mobile phone is the most available household item in Kenya — 94 per cent of homes have one —it is possible for many of these families, especially those with smart phones, to download books and read them from one gadget, thus reducing cost of reading per head.

Private organisations, such as the Canadian charity, KEY School Libraries (KEY stands for Knowledge Empowering Youth), have also demonstrated that philanthropists can put more books in the hands of needy and marginalised children.

In Kenya alone, KEY Libraries, through its sister arm, KEY Kenya, has delivered 45 libraries to over 44,000 secondary school students at an average cost of Sh18,900 per student. This sum includes access to a computer, internet and both physical and digital reading materials.

Meaning that a great deal of work is going on to improve reading. As it is, therefore, only the person who does not want to read isn’t.