Why cholera remains a serious problem in Africa

Cholera is caused and spread by bacteria – specifically Vibrio cholerae – which you can get by eating or drinking contaminated food or water.

It’s an old disease which has mostly affected developing countries, many of which are in Africa. Between 2014 and 2021 Africa accounted for 21 per cent of cholera cases and 80 per cent of deaths reported globally.

In several African countries, cholera is the leading cause of severe diarrhoea. In 2021, the World Health Organization reported that Africa experienced its highest-ever reported numbers – more than 137,000 cases and 4,062 deaths in 19 countries.

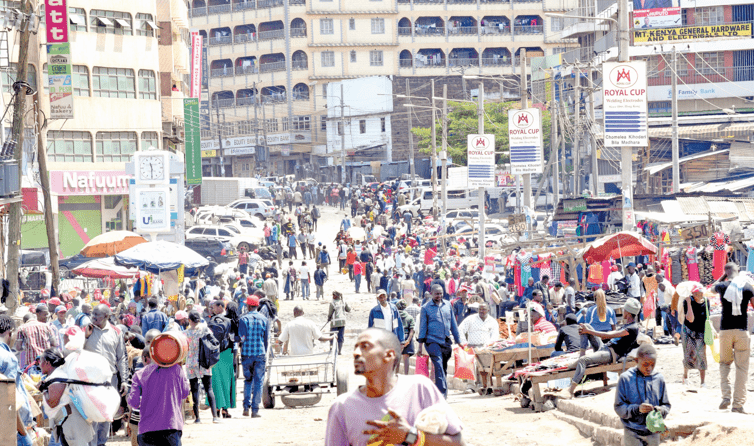

It has persisted in Africa partly because of worsening sanitation, poor and unreliable water supplies and worsening socioeconomic conditions. For instance, when people’s incomes can’t keep up with inflation they’ll move to more affordable housing – often this is in congested, unsanitary settings where water and other hygiene services are stretched to the limit. In addition, in the last decade, many African countries have witnessed an upsurge in migration to urban areas. Many of these people end up in urban slums.

Displaced populations are also very vulnerable to water and food contamination.

It’s important to control cholera because it can cause severe illness and death. In mild cases it can be managed through oral rehydration salts to replace lost fluids and electrolytes. Severe cases may require antibiotic treatment. It’s vital to diagnose and treat cases quickly – cholera can kill within hours if untreated.

In 2015, it was estimated that over one million cases in 44 African countries resulted in an economic burden of US$130 million from cholera-related illness and its treatment.

African governments must acknowledge that the burden of cholera is huge. In my opinion, governments in endemic areas don’t recognise cholera as a major issue until it’s out of control.

The burden of cholera could get worse unless governments put measures in place to control and prevent outbreaks. They need to address water and hygiene infrastructure.

There must also be community engagement. For instance, there is need for widespread messaging that encourages hand washing, boiling of water and other preventive measures. Community health extension workers are key in getting these messages across and distributing supplies during an outbreak.

For the most vulnerable populations, we must apply oral cholera vaccines. Data on cholera hotspots from surveillance studies will be vital to ensure critical populations are targeted first.

There are various brands and variations of the oral cholera vaccine, and they are easy to administer. They have an effectiveness rate of between 60 to 80 per cent but require a yearly booster. There’s not been a concerted vaccination campaign in many countries, however, because governments are not taking the prevention and control of the disease seriously.

Finally, the issue of drug resistance needs to be addressed. Drug resistance has made it possible for these cholera strains to stay longer in the environment.

I was part of a team that conducted a study in Kenya which found that bacteria that causes cholera has become resistant to some antibiotics. Some types of drug resistance are caused by a natural interaction of the Vibrio cholerae bacteria with other drug resistant bacteria in the environment.

Overuse of antibiotics also contributes to drug resistance. Government agencies should develop ways to monitor the use of antibiotics and restrict their prescription. Regulation of antibiotic use in animals should also be improved. Healthcare workers also need to be trained in the proper use of antibiotics.

Have there been any recent advances? One important one has been the development of rapid diagnostic tests that can be used by health workers in the field. These kits are available at costs far lower than lab culture costs. Using them makes it possible to confirm outbreaks promptly.

In addition, more countries are now adopting the oral cholera vaccine for prevention and control.

What is lacking is a concerted effort for all endemic countries to have joint measures to tackle cross-border transmission and persistence of cholera outbreaks.

Some countries are still in denial about outbreaks. This is partly due to fears about repercussions on trade and tourism. But in an interconnected world, this attitude isn’t helpful.

I am optimistic that we can control cholera in African. In the short term this could be done through raising awareness among vulnerable populations and interventions like the oral cholera vaccine.

In the long term, countries need improved water hygiene infrastructure, housing and enhanced socioeconomic conditions. But there must be a strong will by relevant government ministries to work together to realise these goals.

—The writer is the Chief Research Scientist and Director, Centre for Microbiology Research, Kenya Medical Research Institute